The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

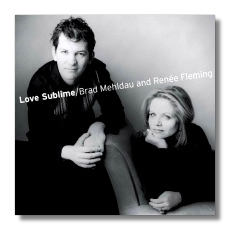

Brad Mehldau

Love Sublime

- Songs from The Book of Hours: Love Poems to God

- Songs from The Blue Estuaries

Renée Fleming, soprano

Brad Mehldau, piano

Nonesuch 79952-2 DDD 48:29

It seems that Fleming's fans would like this to be a classical CD, and that Mehldau's fans would like it to be a jazz CD. It's neither, and that has been a source of frustration to some. The idea of putting one of the world's greatest sopranos together with one of the world's greatest jazz pianists certainly created a set of expectations that, as far as many listeners might be concerned, have not been met. That's ok, though. Mehldau and Fleming have gone their own way and created a CD which ultimately should make their fans respect them even more, if there's still justice in the world.

As a pianist and as a complete musician, Mehldau is maturing nicely. His work with his eponymous Trio has shown him to be an intensely inquisitive and supremely capable performer. In his notes to this CD, he refers to his "deep love of the genre of art song." Jazz musicians are primarily improvisers, however, so how does one reconcile the nothing left to chance precision of art song with the spontaneity of jazz? "Translating an improvisatory style of singing to paper was appealing to me," he writes, "precisely because I've left nothing to chance and there is no improvisation involved." Mehldau's art songs come from a kitchen in which jazz also was being cooked, and although they carry jazz's aroma with them, they are not jazz. Instead, they are his very personal responses to the poetry of Rainer Maria Rilke (The Book of Hours), Louise Bogan (The Blue Estuaries), and his wife Fleurine (Love Sublime).

Really, it's best not to compare the music on this CD to anything, but to hear it for what it is. Mehldau clearly has climbed inside these poems – their rhythms, their sounds, and their meanings – and has composed not so much melodies as musical hyper-recitations to go along with them. Some may feel Fleming's talents have been wasted here, because – except for in Love Sublime - there's little that's conventionally melodic about these settings. Fleming swoons and soars and illuminates the words, but you probably won't find yourself whistling tunes when the CD is over. But that's true of Lulu as well – not that Alban Berg and Brad Mehldau need to be compared to each other – and the worth of Berg's opera is recognized even though it doesn't contain "La donna è mobile," for example. I think if the average listener sits down and gives this CD its due attention while following along with the text, he or she will be impressed by what has been accomplished here, even if it is neither "typical Fleming" nor "typical Mehldau." As one might expect, his piano work here is just as interesting as the vocal lines in the way that it sensitively underlines the texts. As for Fleming, one can tell that she believes in this. Arguably, she's already established her credentials as a jazz vocalist with her Haunted Heart CD, but here she walks the tightrope without a net underneath, and she carries it off handsomely… if perhaps a little preciously, at times. (Like Schwarzkopf and Fischer-Dieskau, she has a tendency to overinflect.)

Jazz is outside the purview of Classical.net, but I feel it is appropriate to note that another Mehldau CD was released on the same day as the one reviewed here. That one is titled House on Hill (Nonesuch 79911-2), and it finds the pianist on more familiar territory, with his regular bass player, Larry Grenadier, and his original drummer, Jorge Rossy. This is a beautiful example of Mehldau's work with the Trio, and it also lets us hear a maturing Mehldau. He's more in control of the material than ever before, and all nine tunes are his own compositions. (Not that I dislike Mehldau riffing on a Radiohead tune, but Mehldau's talents as a composer are considerable, and he need not rely on anyone else's songs to put together a great CD.) His fans should love House on Hill. As for Classical.net's readers, contemporary piano-based jazz doesn't get much better than this, so why not take a chance on something different?

Copyright © 2006, Raymond Tuttle