The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Reich Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

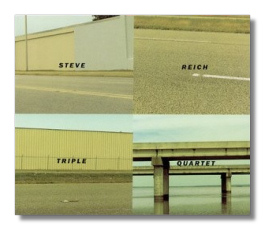

Steve Reich

Triple Quartet

- Triple Quartet

- Electric Guitar Phase

- Music for Large Ensemble

- Tokyo/Vermont Counterpoint

Kronos Quartet

Dominic Frasca, guitar

Alarm Will Sound

Ossia/Alan Pierson

Mika Yoshida, MIDI marimba

Nonesuch 79546-2 DDD 54:09

Summary for the Busy Executive: If you liked it once, you'll love it twice.

The Big Three Minimalists – Reich, Adams, and Glass – have all moved on, each in their own way, from straight-and-narrow Minimalism. Never mind that none of them liked the label; that's what we know that late Sixties-early Seventies music by, and the label will probably stick. Adams, always a very personal poet, has produced what I would call a Deep Image music, after poets like Bly, Kinnell, Stafford, Wright, Merwin, and Hall – music which evokes Jungian depths. Glass now seems interested in abstracting Romanticism, his violin concerto like an outline of the Sibelius. Reich, of the trio, has always built on his previous work. Although you can no longer call his music Minimalist, you can still see the connections. You won't find a break, as you will in Adams and Glass.

The constant in Reich's work has been phase, as it applies to rhythm – particularly fitting for one who began as a percussionist. Beginning with his two tape pieces, "It's Gonna Rain" and "Come Out," which used tape loops and overdubbing on two tape recorders playing at slightly different speeds, Reich very quickly wondered whether humans could produce the same effect unaided. He has expanded the idea of phase and phase shift with almost every work, methodically combining it with other elements. Rather than traditional development, the listener witnesses a process unfolding, playing itself out. Much of Reich's music contains repetition, with subtle changes along the way. It's worth noting that Reich's ideas usually contain enough of interest to bear repeating.

All the pieces here fall to some extent into the categories of arrangements and revisions. The Triple Quartet exists in three versions: string quartet and tape (of the other two quartets), three string quartets, and string orchestra. Kronos, who commissioned the piece, perform against themselves on tape. Reich wrote this work to some extent under the inspiration of the Bartók fourth and the Schnittke second quartet. The energy of those pieces inspired him most.

It's an interesting point. Both Reich's models depend on strong contrast to generate and release their energy. On the other hand, black-and-white contrast has never been a feature of Reich's music, and it's not here. Listening to Reich's music shares a lot with watching the shifting shapes of clouds. Little elements gradually changing add up to big changes over an extended period of time. Nevertheless, Reich does work into each of the quartet's three movements features of contrast, particularly shifting tonal centers – a big deal, since I can't readily think of another Reich piece that does this. Reich cycles through e-minor, g-minor, B Flat Major-minor, and c-sharp-minor tonalities (alert listeners will spot the outline of a diminished-seventh chord) to distinguish the large sections of each movement. Because of the harmonic progression, this work seems to me the closest Reich comes to the classical tradition.

In 2001, Dominic Frasca arranged Violin Phase from 1967 for electric guitar and "virtual guitars" on tape. In this very early piece, one can hear fairly clearly the base on which Reich built his musical language. We listen to four parts getting out of and coming back into phase. The tonality never changes, so we wind up with a study in mind-boggling polyrhythms. It amazes me that the piece doesn't bore me to tears, especially in its electric guitar version. The instrument simply doesn't strike me as expressively varied. Nevertheless, there's always something new in the piece, some new emphasis that holds my attention. But that's how it is with me and most of Steve Reich's music.

The version recorded here of Music for Large Ensemble differs from the 1977 original and from the 1979 recording. Pierson changed the orchestration slightly, mainly making the voice and sax parts optional, with the composer's blessing. The piece delights with a jazzy three-four. Here, the phasing occurs solely through human means, as the music gets pushed bit by bit "ahead" of the bar line. The basic musical cell varies just enough, but it also contains a lot of interest in its own right. The idea can take a lot of repetition, although this is one piece that gains a great deal from the spatial aspects of the sonic image. So either put yourself in stereo listening position or wear earphones.

Tokyo / Vermont Counterpoint arranges the 1977 Vermont Counterpoint. The original used a battery of flutes and piccolos. However, Reich's music is essentially rhythmic, and percussionists have tried to adapt the piece. However, the decay on real xylophones and marimbas is so long that the counterpoint gets muddied. Yoshida solves that problem by using virtual marimbas, where the decay can last as long or as short as she wants. For me, her performance improves in every way on that of the earlier recording, from the DG Reich boxed set, led by Ransom Wilson. It's more sprightly, for one, lighter, less self-important. I imagine Reich writing it on a kind of busman's holiday.

I am almost always amazed at how high the standards of playing have risen not only in my lifetime, but in the past thirty years. I remember when players gritted their teeth before tackling something like Reich's Music for 18 Musicians. Now they actually seem to have fun. A wonderful set of performances, and a jewel in Nonesuch's ongoing commitment to Reich's music.

Copyright © 2005, Steve Schwartz