The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Mahler Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

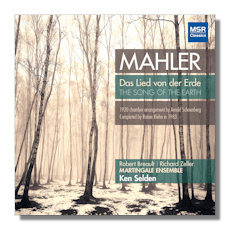

Gustav Mahler

Das Lied von der Erde

- Chamber arrangement by Arnold Schoenberg, completed by Rainer Riehn

Robert Breault, tenor

Richard Zeller, baritone

Martingale Ensemble/Ken Selden

MSR Classics MSR1406 72:33

Summary for the Busy Executive: Lean Lied.

Over roughly three years, beginning in early 1921, Arnold Schoenberg headed the Verein für musikalische Privataufführungen (society for private performances of music), dedicated to the performances of relatively new and contemporary work. Audiences came from subscribers only, and the press was excluded. One level of subscribers paid according to their means. This ensured that only those genuinely interested would attend. Musicians rehearsed their programs thoroughly, to give audiences the best shot of comprehending the new. Due to budget constraints, performing forces were fairly modest, and orchestral works given in chamber arrangements. Schoenberg banned his own music from performance. However, programs included, among many others, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók, Ravel, Webern, and Berg.

In part, the Society aimed to show the continuity between new music and that of the late Nineteenth Century. Mahler stood as a special case – obviously late Romantic, but also Modern. As late as the Fifties, a critic could safely trash him. Schoenberg began to arrange Das Lied von der Erde in 1920 for singers, string quartet with bass, woodwind quintet, piano, harmonium, and percussion, but the Society folded due to money problems before he could finish. Rainer Riehn completed Schoenberg's sketches in 1983.

Now, of course, the battle for Mahler has been won, and we are used to hearing him played by large orchestras. The chamber arrangement therefore initially may strike some as a shock. The oceanic opening to "Das Trinklied vom Jammer der Erde" (the drinking-song of the sorrow of earth) with only a solo horn – because the full brass would overwhelm the small group – forces one to quickly readjust one's mental scale.

To my amazement, I don't miss the full orchestra at all. Schoenberg, one of the great orchestrators, manages to suggest the original colors with a smaller group. However, we get a far clearer view of the bones of the work as well. To those detractors who derided Mahler as a "mere" orchestrator, Schoenberg's version reveals the substantial edifice of Mahler's composition. I wouldn't want this as my only Lied, but Schoenberg's arrangement has its own aesthetic validity, like Ravel's arrangement of Mussorgsky's piano masterpiece, Pictures at an Exhibition.

Several others have recorded this version. My current favorite comes from the Swedish label BIS, with Osmo Vänskä. Most of the others I've heard are marred by poor soloists. This MSR disc falls between the Vänskä and those others. Again, it comes down mainly to the tenor soloist. Robert Breault has a smallish voice, but that doesn't count against him here, since he doesn't have to compete against a super-sized orchestra. However (and this may seem nit-picky to some), I quibble with his vowels, which tend to the overly-bright, so that he can get more ring into his voice. However, it distorts the German. "Der," for example, becomes "dayeeere." You might be able to get away with stuff like this in opera, when the libretto quality is so low and nothing is at stake except whether the soprano will make the high D so nobody cares, but not here. Baritone Richard Zeller does far better and declaims his text with the intelligence of a superior Lieder singer. Ken Selden turns in a superior job wrangling the instrumentalists, and together they inject the work with sensitive phrasing and handling of dynamic transitions, soft to loud and back again. I find them a bit hectic in the opening number, but overall this is a graceful reading.

Copyright © 2015, Steve Schwartz