The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Cage Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

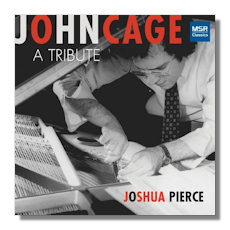

John Cage

A Tribute

- Four Walls

- Primitive

- In the Name of the Holocaust

- Quest

- Our Spring Will Come

- Piano Sextet "Prelude for 6 Instruments in A minor" **

- Ophelia

- Sonatas & Interludes for Prepared Piano

- 3 Early Songs *

- 2 Pieces for Piano (1946)

- Music for Marcel Duchamp

- Spontaneous Earth

- 3 Easy Pieces for Piano

- The Unavailable Memory of

- 2 Pieces for Piano (1933)

Joshua Pierce, piano & prepared piano

* Robert White, tenor

** American Festival of Microtonal Music Ensemble/Johnny Reinhard

MSR Classics MS1400 155:44 2CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Surprise!

I've usually said that I'd rather perform and read about John Cage's music than actually listen to it. This CD gathers together early Cage, written before 1950, and some of it is eminently listenable. Cage grew up in California, away from the taste-making centers of Boston, New York, and Chicago. In such an environment, he – like Henry Cowell, another radically innovative Californian – could think about music with few cultural strictures about "proper" or "real" music. He studied with both Schoenberg and Cowell, although Cowell's example proved more congenial. At one point, Cage explained his development as the result of finding ways to make music around his limitations. He felt he wasn't a great contrapuntalist, harmonist, or melodist. What was left? Rhythm, for one, as well as the world of sound in general, both natural and synthesized. As far as I can tell, none of the pieces here result from Cage shooting dice. The works divide into Very Early, Schoenberg, Early, and Pre-Aleatoric.

Cage wrote many of these pieces for dancers, most notably Merce Cunningham. Four Walls (1944) actually has a plot, about a dysfunctional family. Since I've never seen the dance, I can't testify as to how well the music serves the drama. For those who think Cage inseparable from tape recorders and stunts, Four Walls challenges the preconception. The sections of the score divide roughly into chorales and ostinatos. In the chorales, the Satie of the Rosicrucian pieces gets bathed in Coplandian harmonies (lots of ninth chords, widely spaced). An American composer could escape Copland only with difficulty during the Forties. However, the Satie connection is new. You would look in vain for harmonic resemblances to the Frenchman. It's more a matter of rhythm and expression – austere towers of sound, stark against a background of silence. As in Satie, silence assumes as much importance as sounded notes. Some of those silences go on for a far piece. I should say that Cage came down a bit hard on himself as a melodist. Even though he deals almost exclusively in vertical sonorities, his "chord-melodies" reach high levels of expressiveness. The ostinatos are highly percussive and dissonant. They remind me of the "barbarism" of the Twenties, with a significant difference. The older scores aimed to goose the listener's excitement, which implies a rise over a longish span. Cage's ostinatos are loud and heavy, but curiously non-arousing, beyond the first minute or so. They may well have caused the first audiences more problems than the chorales, but they ultimately proved less radical. More on this later.

The very early pieces like the 3 Early Songs (poems by Gertrude Stein), the 3 Easy Pieces, and the early 2 Pieces for Piano – written 1933-35 – show Cage's predilection for simplicity and few notes. The fanciest he gets are in the 3 Easy Pieces, where he puts together a little suite of a canon (or round), a two-part invention, and an "Infinite Canon," to wind up. Around 1935, Cage studied with Schoenberg – practically his antithesis – without necessarily taking up serialism or textural complication. Quest and the second of the Two Pieces (1935) come closest to Schoenberg's piano music, but Cowell counts as a large influence as well.

In the Thirties, Cage began to "prepare" pianos by sticking things like screws, bits of plastic, and erasers among the strings – in my opinion, an extension of Cowell's avant-garde performance techniques. Cage specifies not only the materials, but also their precise placement (the particular string, above or below the dampers, and the precise distance away from the dampers). This isn't as haphazard as it sounds. The sonorities are often quite beautiful and must have come from rigorous experimentation. In the Name of the Holocaust (1942), for example, has nothing to do with the Nazi extermination of Jews, gypsies, homosexuals, and other "undesirables." It actually comes from a pun in James Joyce's Finnegan's Wake: "in the name of the Holy Ghost"/"holocaust." The piece beautifully evokes Roman Catholic ritual. You hear chanting monks and swinging bells echoing through a stone cathedral. However, the major Sonatas and Interludes (1946-48) virtuosically varies the sonorities of the instrument through 19 separate pieces. Of course, the percussive element gets emphasized, but it's more like the expressive and dynamic range of a gamelan orchestra or sometimes a harpsichord, from delicate on up, rather than the monotonous level of a steel foundry.

I'll write briefly about the Sextet, since a chamber work for traditional instruments occurs so rarely in Cage's output. Oddly enough, it strikes me as one of Cage's more radical works, pointing the way to the aleatoric period. Incidentally, Cage's "randomness" is never truly random. The results may be random, but the process that generates the result is usually strict and unvarying. The most expressive device into the piece is the rest, which isolates almost every gesture, like the surprising intrusion of a "real-life" sound against various synthetic ones, including those made by conventional instruments. After all, a violin is in a certain sense an extremely limited synthesizer, although so old we accept it as "natural." At any rate, the sharp separation of events create an emotionally-distant austerity.

Robert White does well enough in the Early Songs, although his voice has aged. Still, as a singer he was mostly about musicianship, anyway. That hasn't diminished. The instrumentalists in the Sextet are rhythmically in the pocket, which – excepting a brief and surprisingly warm legato passage on the piano – is all that's required. However, pianist Joshua Pierce emerges as the hero of this project. Cage doesn't often provide expressive directions, leaving the performer to come up with emotional images. He goes beyond a blunt light vs. serious. As I've said, he conjures up the image of Roman Catholic rites in Name of the Holocaust. However, he really shines in the Sonatas and Interludes, where he gives the sonorities their own psychological space. Who knew, for example, that Cage's music could be humorous or whimsical? I rate his interpretations over the classic performances by David Tudor and Cage himself. Pierce has obviously lived with this music a long time.

Copyright © 2014, Steve Schwartz