The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Schubert Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

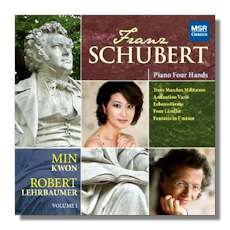

Franz Schubert

Piano Four Hands, Vol. 1

- 3 Marches militaires, Op. 51, D. 733 (c. 1822)

- Andantino varié in B minor, Op. 84 #1, D. 823 (1827)

- Duo in a "Lebensstürme", Op. 144, D. 947 (1828)

- 4 Ländler, D. 814 (1824)

- Fantasia in F minor, Op. 103, D. 940 (1828)

Min Kwon & Robert Lehrbaumer, piano

MSR Classics MS1345 61:52

Summary for the Busy Executive: Lovely.

Visiting a record store (remember those?) the other day, I overheard a customer complaining to a clerk about the availability of a CD. I thought to myself, "Rich people's problems." We have become a bit spoiled by the availability of music to us – live, broadcast, CDs, MP3s, streaming, even LPs – not only in our houses, but in many cases in our cars or wherever we happen to be, swaying to the iPod even while waiting to cross a busy street.

But this state of affairs has risen only recently. A century ago, if you wanted to hear music, you mostly had to buy a ticket (either literally or figuratively) or play it yourself. Music-making in the home took place a lot and persisted long after the introduction of records and the radio. I can still remember my family singing around a parlor spinet and long drives where "Daddy sang bass and Mama sang tenor." In the Nineteenth Century, the piano invaded most middle-class homes with social and musical ambitions, and some family member "took" lessons. The piano was to the Victorian parlor as the iPod is to the shirt pocket. Publishers thrived, not on the orchestral scores and massive oratorios of great composers, but on the bales of popular piano music and parlor songs they turned out.

Four-hand piano music also enjoyed a certain popularity, so much that major composers, as eager to make a Thaler as anyone, wrote for the combination. Because a piano represented a sizeable chunk of change, piano four-hands sold more than two-piano. The genre comprises three flavors: "sociable," "studious," and "striving." Composers wrote for all three. Four-hand music belonged to at-home musicales. Among other things, it provided an excuse for a young man and a girl to surreptitiously (and deliciously) touch, especially where the right hand of the secundo player crossed over the left hand of the primo. Such were the days! In the area of "sociable," the Dvořák Slavonic Dances and Legends originally began in four-hand format. The "studious" includes those arrangements of larger works to disseminate the music to places without the requisite musical resources. Brahms arranged all of his symphonies, for example, for the duet. By "serious" I mean those major works intended for four hands, although these usually came out for two pianos. Brahms began a sonata for two pianos, which became something else, but – unusually for Brahms, who compulsively destroyed early drafts – the original manuscript remains. Furthermore, composers wrote to several markets. Debussy produced the sociable Petite Suite and the serious En blanc et noir.

Schubert wrote roughly forty works for piano four-hands. A lot of it falls into the "sociable" bin, but he also has a number of "serious" pieces. The program on this disc gives us a mix of the two.

Let's take the "sociable" first. The 3 Marches militaires include one of Schubert's hits, the first, known as the Marche militaire. Schubert is one of the earliest composers to see the symphonic possibilities of the march, as well as its emotional range. Mahler, of course, views the march in much the same way. These Schubert marches are military, in the sense of the parade ground rather than the battlefield. These soldiers march within the frame of a Biedermeier print. The four Ländler (countrified waltzes) get just sixteen measures each, but you shouldn't quite dismiss them as fluffy fluff. Schubert has, through a canny choice of keys and small recurring gestures, fashioned an extremely unified work, that in its very modest way points to a symphonist.

The remaining pieces I'd call "serious." Schubert was the major composer after Mozart to produce first-class original work for four hands. A small gem, the Andantino varié consists of a theme and four variations. The theme, deceptively modest, carries some harmonic interest. It begins in harmonic ambiguity and in its second part makes some tasty moves to the relative major key of D. The first two variations are pretty straightforward. Variation 3 puts the theme in an inner part, with swirling canonic lines surrounding it. Variation 4, in major mode, mines a vein of tenderness later exploited by Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Brahms. Hearing it as early as Schubert startles a bit, like hearing a psychic accurately predict the future.

The Fantasia and the Duo come from the last year of Schubert's life. By this time, he had absorbed those lessons of Beethoven he could use and had begun to move in a new direction, especially in matters of form. The fantasia becomes a major genre for him, probably reaching its height in the "Wanderer" Fantasy. Furthermore, Schubert, I think, had a phenomenal ear for harmony, and his music depends on modulation to a greater extent than Beethoven's. Despite the difference in titles, both are essentially fantasias with links to the symphony. The f-minor Fantasia consists of four movements, corresponding to sonata allegro, slow movement, scherzo, and sonata finale, but with strange proportions: a very brief slow movement and an extended scherzo. Despite the title Fantasia, Schubert has written a very tight work. The first movement works with two themes – the first a lyrical minor and the second more assertive and more structural. Imitative, sometimes canonic writing becomes pretty much the norm of the entire fantasy. In this movement, Schubert's amazing harmonic sense stands out. At one point, he modulates from f-minor to f#-minor, quicker than you can blink – the composer's equivalent of a diver's triple gainer. The second movement uses the rhythm of a French overture. Without quoting any motive from its predecessor, it largely keeps the harmonic structure of the first movement. With the scherzo, a fast waltz that forecasts the opening movement of the Tchaikovsky Serenade for Strings and echoes the scherzo of Schubert's Ninth, Schubert kicks into higher gear, with more canonic writing and even mirror writing (the bass inverting the melody, as both play at the same time). I love this movement's energy and the piquancy and giddiness of the main idea. At the finale, the themes of the first movement return, with the second becoming a tempestuous fugue. The piece ends with the opening lyrical theme.

The Duo in a is also known by the nickname "Lebensstürme" (storms of life), bestowed by the first publisher more than a decade after Schubert died. In contrast to the containment of the Fantasia, the Duo hosts a swarm of diverse ideas. Indeed, it threatens to sprawl, but somehow never does, mainly due to a masterful use of some very distinct motifs, including an angry fanfare, a chorale, and a "closing" idea. Structural strangeness also clings to this piece. It's vaguely in sonata form, but this time not only the proportions but the placement of sonata components run outside the usual. The exposition is not only very long, but repeated, delaying the development and considerably shortening an already-abbreviated recapitulation. The development largely consists of modulation to remote keys rather than varying basic ideas. The chorale comes in especially handy. Robert Lehrbaumer's liner notes regard the chorale as Bruckner before the fact, but you can find many examples of this type in Schubert himself. To me, it's echt-Schubert. The keyboard writing unabashedly evokes the symphony orchestra. You can hear various "sections" chiming in. Schubert pushes passion to the limits of good taste without crossing over. Storms and stresses galore.

Min Kwon and Robert Lehrbaumer play as one organism. Kwon usually takes primo and Lehrbaumer secondo, but they do switch on a couple of pieces. I tried to discover any difference in tone or approach. Any distinctions are extremely subtle ones, with Lehrbaumer slightly drier and more detached in his attack. However, they make very clear the architecture of each piece and always let you hear the important line, no matter how buried in the texture. The performances to me get to the essence of Schubert as a composer – part naïve bourgeois, part visionary titan. This recording brings smiles to my face every time I listen to it.

Copyright © 2012, Steve Schwartz.