The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

J.S. Bach Reviews

Beethoven Reviews

Schumann Reviews

Brahms Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

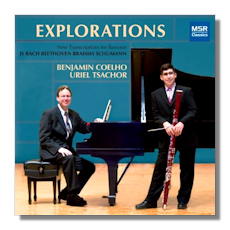

Explorations

Transcriptions For Bassoon

- Johann Sebastian Bach: Sonata in E Flat Major, BWV1031

- Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonata in D Major, Op. 102/2

- Robert Schumann: 3 Romanzen, Op. 94

- Johannes Brahms: Sonata in F minor, Op. 120/1

Benjamin Coelho, bassoon

Uriel Tsachor, piano

MSR 1237 59:20

Summary for the Busy Executive: Amazing.

A Rodney Dangerfield of instruments, like the tuba, the bassoon doesn't get much chance to solo, and when it does, it usually plays a comedy part. Certainly, major-league composers from Beethoven on have written far fewer things for it than for clarinet, flute, and oboe. Indeed, I can think only of a lovely sonata by Saint-Saëns and a meditative one by Hindemith, neither of which you'd call standard repertory. Perhaps composers think of it either as a utility instrument in a wind quintet or as a momentary "color" in the orchestra. Certainly, that's how I as a listener tend to regard it.

Consequently, none of the pieces here were originally for bassoon. The Bach is a transcription of a flute sonata, the Beethoven of the fifth cello sonata, the Schumann of a set for oboe (or clarinet), and the Brahms of the second clarinet sonata. Normally, I'm no fan of this activity, but bassoonists need repertoire. So the question comes down to whether these things work on their own terms or whether the performer convinces you.

Coelho is nothing short of revelatory. In addition to playing, he made all the transcriptions, and I can't praise him any higher in both activities than to say he makes you ask why nobody has seized the possibilities of the instrument before, because he seems to have raised what is possible. I know nothing of bassoon technique or even the problems in playing the instrument. I assume the bassoon shares features with the oboe, and since I know so little about the oboe as well, that doesn't help. Consequently, I can tell you only what I hear.

Bach may or may not have written the sonata ascribed to him. We know only that the earliest manuscript, not in his hand, shows up nevertheless in his circle. If real Bach, it's Bach in a lighter, almost galant vein. Coelho and his musical partner, Uriel Tsachor, spin delicate, sprightly webs of sound in the first movement. The second movement, in slow triple-time, sends out long lines. The finale to me sounds more characteristically Bachian. The counterpoint, particularly the crossing of lines and registers between wind and keyboard, strike me as typical of Bach.

For some reason, only the odd-numbered Beethoven cello sonatas (of five) appeal to me. I enthuse over 1, 3, and 5, and remain totally indifferent to 2 and 4. Periodically, I go back for another try, but so far the sun hasn't broken through. The three I like I consider the best of any, except Bach's. In the fifth, the first movement sounds the trumpets. The second, another wonderful Beethoven adagio, seems to come from the opera stage, with a pastoral middle, reminiscent of a musette. Coelho shines here with a near-seamless line, full of subtle shades. The finale, a fugue, inaugurates the attraction of the form to the composer in his later years, culminating in the monuments of the Missa solemnis. These fugues, unlike the composer's early examples, sound like no fugues written before. It's as if the late Beethoven sonata and the fugue had a baby. The twists of phrase, the continual pressure of the phrase against the beat, all threaten to derail the music, but somehow never do.

Schumann wrote his 3 Romances in 1849, an unusually productive year. They didn't receive a public performance, however, until 1863. Still, they must have had some success among amateurs, since Schumann wrote two versions, one for oboe and one for clarinet, and the publisher provided an arrangement for violin. Not sonata and not quite song, they belong to the genre of "character piece," of which Schumann was a master. Each one seeks to establish a mood. The first sings prettily in a minor key. The second seems to linger over light regrets. The third has that Eusebius-Florestan duality – meditative and assertive by turns – which we find throughout Schumann's work.

To me, late Brahms eludes most performers' grasp. His forms become freer, thus harder to bring into focus, and he really hits the middle and low sonorities, which make for thick textures. The clarinet sonatas I've never cared for in their original form. This may come down to the fact that I've never heard a clarinetist I've liked in these works – even favorite clarinetists in other works. I much prefer the version Brahms made for the viola. Coelho and Tsachor do okay in the first movement, but for me the last three movements offer the greater challenges. Here, the bassoon has it all over the clarinet. Its brighter tone and deeper register seem made for the Brahmsian textural purée of the second movement. The third movement swings between a light, almost rustic dance and Schumannesque inwardness. Coelho and Tsachor capture both. The finale skips, but frequently rises to passionate and eloquent outbursts.

Coelho plays these things as if the composers actually had written them for the bassoon. He convinces you utterly. Tsachor contributes equally to the interpretations and even hints that he can do much more. I'd love to hear him all by himself.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz