The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

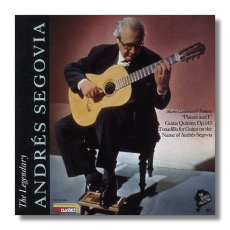

The Segovia Collection, Volume 8

- 10 Pieces from "Platero and I"

- Guitar Quintet

- Tonadilla for Guitar on the Name of Andrés Segovia

Andrés Segovia, guitar

Members of the Quintetto Chigiano

MCA Classics MCAD-10056

As late as the 60s, American Decca had a small but rather select group of classical performers, including not only Segovia but also Szymon Goldberg and Rosalyn Tureck. Segovia, in particular, recorded (and sold) quite a bit. In fact, he became less of a performer and more an icon as his career continued. Just as Landowska unquestionably meant the harpsichord, Heifetz the violin, and Casals the cello, Segovia meant the guitar.

There have been better players than Segovia even among his contemporaries, just as there were better cellists than Casals (Feuermann, for one). Yet it doesn't seem to matter. Certainly no one brought the guitar to notice as he did. Furthermore, Segovia committed considerable energy and money to expanding the original repertoire for the instrument. Unfortunately, Segovia, like Heifetz, had very conservative musical tastes. Much of what both commissioned was insipid or outright dreck. Still, the guitarist did commission a repertory staple, Castelnuovo-Tedesco's Guitar Concerto in D of 1939 – such a hit, that Segovia, until practically the composer's death, kept asking for new work.

It's hard for me to say why Segovia inspired so many composers and players or enthralled so many listeners. In an age of such wizards as Julian Bream, the Romeros, and the Australian John Williams, Segovia was technically small potatoes. Even in this recording, he plays like a person trying to keep his balance: he never lands on his can, but he's not comfortable standing up either. One hears awkward hesitancies as well as the music almost slipping away rhythmically before he catches himself. He also produces more squeals, smudges, taps, and buzzes at the fingerboard than we expect from players today. Obviously, Segovia gave us something more important than technique. Segovia could take music beyond notes into the heady realms of personality and emotional meaning. He particularly excelled at creating a meditative mood, and often with inferior goods.

The Italian Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco studied with Pizzetti. In 1939, he was forced to flee Italy (he was Jewish) and came to the United States to settle finally in Los Angeles. Extremely well-read, he found his main inspiration in literature, particularly in Shakespeare, with two operas (Merchant of Venice, Much Ado About Nothing) and settings of most, if not all, of the lyrics. Besides many pieces for Segovia, he wrote a concerto for Heifetz (subtitled "The Prophets"). He also scored several negligible movies, the least forgotten of which was a collaboration with Miklós Rózsa on Ronald Coleman's "A Double Life." His music is mainly Impressionist, expertly made, and perhaps too refined for its own good. There's no audacity. You won't find a Heldenleben here. He even lacks the vivid orchestral imagination of a Respighi, whose basic idiom he shares.

"Platero and I" sprang from a literary source: poems by the Spanish Nobel Laureate Juan Ramon Jimenez. The album contains ten of the original eighteen pieces, and the liner notes give the gist of the poems. Not having read the originals, I can't comment on how closely the composer has followed the poet. I can say, however, that I preferred to forget the little summaries and listen to pure music. I found the morceaux pleasant, but too similar. It's *all* thoughtful, sweetly nostalgic, tender, and heavily dominated by the Spanish idiom. A few of these works go a long way.

Somewhat more successful is the Tonadilla on the Name of Andrés Segovia. Castelnuovo-Tedesco assigns one note to each different letter in the name and thus builds his main theme. Its interest lies in the ingenuity of the composer in taming the theme.

For me, the most engaging (and, not coincidentally, most extroverted) work was the Guitar Quintet. Despite its echoes of the Debussy and Ravel string quartets, the interplay among all the instruments engrossed me. The composer gives everybody something interesting to do. The guitar never merely accompanies the strings, and the strings never stand around like spear-carriers while the guitar hogs the spotlight. Castelnuovo-Tedesco works this equality mainly through imitative counterpoint and frequent changes of texture, number of sounding instruments, and so on. In fact, to all you string players lucky enough to be in quartets, make an effort to find a guitarist. This must be a gas to play.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz