The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Shostakovich Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

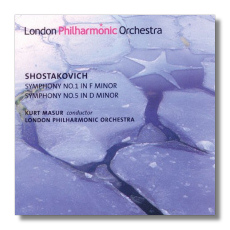

Dmitri Shostakovich

- Symphony #1 in F minor

- Symphony #5 in D minor

London Philharmonic Orchestra/Kurt Masur

London Philharmonic SACD LPO-0001 Hybrid Multichannel

The 1979 book Testimony – The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovich by Solomon Volkov has had a pervasive and, I think, negative influence on the interpretation of Shostakovich's music. I don't want to rehash the claims in the book, but suffice it to say Shostakovich is alleged to have asserted, among other controversial things, that there are hidden messages – mostly anti-Soviet messages – in many of his works. The Fifth Symphony, for example, is supposed to end not triumphantly, but resounding forced rejoicing – forced, that is, by Soviet authorities. I believed Volkov's book was completely authentic when I first read it in the early-1980s, and most musicians apparently did as well. Interpretations of the finale to the Fifth, for example, have slowed down dramatically in the post-Volkov era, stretching from the standard ten or eleven minutes to twelve or thirteen or even more (as here).

In recent times more and more evidence has emerged to support the notion that Volkov's book contains fake interviews with the composer. Musicologist Laurel Fay has been the main proponent of this view and her arguments are based on solid research and seemingly irrefutable logic. I've resisted her stance on this book for a long time, accepting the views of Allan Ho and Dmitry Feofanov, but now I am convinced she is right. But whether she is or is not should actually not be of great consequence in the interpretation of Shostakovich's music. If, for example, the ending of the Fifth truly has a hidden message or meaning, it's still pretty bland, rather bombastic stuff. Why slow down the tempo? Does that approach draw out some angst that faster tempos miss? I don't think so.

The famous Bolero-like buildup in the Seventh Symphony, which Bartók deftly parodied in his Concerto for Orchestra, is another case in point, if I may digress for a moment. It also is supposed to have a hidden message, but whether it does or does not, the music here is hardly profound or well-crafted. If Shostakovich is portraying the 'banality of evil' or just writing patriotic music to resist German aggression, he carried out the task by taking a jingle-like tune and building it into colorful bombast and little more. You can slow this down or speed it up and it doesn't get any better. It's catchy, I'll concede, even rousing – but, alas, for a mere listening or two!

Back to the issue at hand… The Fifth Symphony's least effective movement is, not surprisingly, the finale, and one treatment it doesn't need is moderate or slow pacing. Masur clocks in at a whopping 13:48, with the closing pages taken at an incredibly slow tempo. Bernstein, in his well-known 1959 recording, brought in the finale at 8:55. I'll concede that might be a bit on the brisk side, but even the composer's son Maxim, in his Melodiya recording from around 1970, was about two minutes quicker than Masur, and iconic Soviet conductor Kyril Kondrashin was quicker still. I can only guess that Masur truly believes there's something Volkovian lurking beneath the surface of this music and thus plumbs it with a Mahlerian fervor to dredge it up. But he unearths nothing.

The rest of the symphony, however, goes reasonably well. The work was recorded at a low level, so the listener should crank up the volume a bit. That still may not compensate for the fact that Masur draws much soft playing from the LPO, pianos and pianissimos seeming to permeate so many passages, especially in the third movement. It's all quite splendidly brought off though, and the performance as a whole is very well thought out: I may not agree with some of Masur's tempos and other touches, but the playing and interpretation are carefully molded and those listeners who share Masur's view of the work (and of Volkov) should be enthralled by the performance.

Incidentally, if we can all suppose for a moment that Volkov's book is, in fact, genuine and Shostakovich did indeed plant messages of protest in his music, can we then view the composer as a bona fide dissident? I can only say that such covert dissent hardly displays the kind of courage Andrei Sakharov and many other Russians exhibited at great expense to their careers. Yet, I must say that, musically speaking, it doesn't matter whether Shostakovich was privately a dissident or a composer complying with the dictates of the state. Either circumstance can't lessen or increase the artistic value of his music. He was a major composer in any event.

The performance of the First Symphony here is more convincing than that of the Fifth. The opening of the first movement recalls Till Eulenspiegel, Masur pointing up this kinship more deftly than any other conductor I've encountered in the work. Again, the playing is subtly nuanced and Masur's view of this attractive piece is well-shaped and brilliantly executed by the LPO. The sound is vivid, too. This is apparently the first release on the London Philharmonic Orchestra's own label, and on the whole this magnificent ensemble – founded in 1932 by Sir Thomas Beecham – can be proud of this issue. Both performances were taken from live concerts given from January 31 through February 3, 2004 at London's Royal Festival Hall. Despite my reservations about the Fifth, most listeners should find these readings at least provocative, if not fully convincing.

Copyright © 2005, Robert Cummings