The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

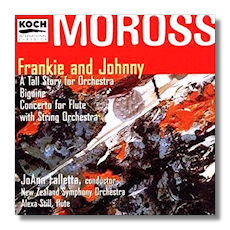

Jerome Moross

- Frankie and Johnny

- Biguine

- A Tall Story for Orchestra

- Concerto for Flute with String Orchestra*

Alexa Still, flute

*New Zealand Chamber Orchestra/JoAnn Falletta

New Zealand Symphony Orchestra/JoAnn Falletta

Koch International 3-7367-2

Summary for the Busy Executive: I ain't gonna tell you no fable – a delight.

During the 1930s, Copland formed a group of young New York composers. The group included Elie Siegmeister, Israel Citkowitz, Vivian Fine, Henry Brant, Arthur Berger, Bernard Herrmann, and Jerome Moross. The members were too diverse to cohere as a group, and I, for one, can't imagine the explosive Bernard Herrmann with the tact to remain a member. But even here, Herrmann did gain a close friend in Jerome Moross, which speaks volumes for Moross's conviviality, as does the music, by the way.

Part of the left-wing movement during the 1930s translated itself in American music into the desire to invent an accessible, even popular, classical style. The most publicly visible example, Copland moves from the "difficult" idiom of the Piano Variations and Short Symphony to his brand of Americana in works like An Outdoor Overture and Billy the Kid. The younger man, Moross moved more quickly, and he did have Copland's example before him. It took him only one large-scale work – Paeans – to turn from hieratic to accessible. Yet he didn't ape Copland – or Virgil Thomson, for that matter. Moross found a distinctive voice very early – a mix of folk song, 1930s pop, and turn-of-the-century ragtime, cakewalks, two-steps, fox-trots, vaudeville turns, and proto-jazz – rhythmically lively and as refreshing as a really good glass of water. For the most part, Moross's output divides neatly into chamber music and theater work. As a composer, he's fairly modest in his aims. He doesn't wish to conquer. Moross's music is mainly charming and well-made, and the chamber music especially reminds me of – I hate to say it, since many will at this point roll their eyes at the ceiling – Mozart. Both composers show a clarity of form, equal distribution of interest among parts, suitability of music to instrument, economy of expression, and, despite whatever psychological depths they plumb, a view of chamber music as an opportunity for players to get together. Mozart's music for me may go deeper, but Moross's surface is just as beautifully worked.

Moross's theater career included Broadway reviews (Parade), ballets (Ballet Ballads), landmark film scores (notably The Proud Rebel and The Big Country), unfinished Broadway shows (Underworld, about gangster Dion O'Banion), and one of the finest Broadway musicals, The Golden Apple (available on RCA 09026-68934-2). Funded by the Guggenheim Foundation, to lyrics by poet John LaTouche (who also worked on Moross's Ballet Ballads), this satiric update of Homer's Odyssey to the time of the Spanish-American war pretty much flopped on its only run. One can make a strong case, however, for its influence on Leonard Bernstein's Candide (which also failed during its initial run). Its strong, bouncy score produced one genuine standard – "Lazy Afternoon" – and it has since become an icon to the hard-core Broadway cult. Collectors hunt the original cast album. Given the current state of affairs, you almost can't believe Broadway ever hosted anything this good.

Moross wrote in almost all forms, including a Symphony #1 recorded by JoAnn Falletta and the London Symphony on Koch 3-7188-2H1. However, the closest thing he has to a classical hit is the ballet Frankie and Johnny, written for Chicago choreographer Ruth Page and recorded at least once before. It's the familiar story and the familiar lyrics, but after an initial tip of his hat to the original tune, Moross is off and away on a witty exploration of early blues and ragtime, all with his own music. In fact, one hears germs that found their way into Bernstein's (later) On the Town dance numbers. There's a sense of a "Bernstein before there was a Bernstein" throughout. The most interesting part of the "orchestration" is a women's vocal trio of Salvation Army officers, who sing mainly against type – blowzy and frowsy or with a knife edge. One enjoys such a good time with the piece, that Moross's simultaneous near-encyclopedic survey of modernist devices slip by as such, and registers expressively – exactly as it should.

Biguine (nobody knows why Moross spelled it this way) shows the 1930s U.S. fascination with Latin rhythms, from Gershwin and Cole Porter to Copland and Paul Bowles. Compared to Porter's well-known examples, Biguine insinuates more while remaining rougher. Porter really never uses the beguine as anything more than a piano vamp, while Moross builds the rhythm contrapuntally, from many different melodic bits. The orchestration emphasizes the fragments, as no instrument seems to play a complete phrase. We get a kaleidoscopic conversation among many instruments and sections.

The inspiration for A Tall Story comes from Moross's cross-country trip by auto from New York to Los Angeles, where he would work in movies. The landscape, the huge open spaces and "big sky" of the American West, apparently bowled over Moross – like Copland, a composer from Brooklyn. I find it interesting to compare Copland's and Moross's evocation of the West. To me, Copland largely plays cowboys-and-Indians. Everything is mythic and bigger than life. On the other hand, people rather than archetypes inhabit Moross's West. Moross himself traced his idiom to the folk songs he heard at summer camp. He didn't have to find the tunes, as Copland did to a large extent in tune collections. The songs were already part of him and tied to specific places and figures. As far as I can tell, however, all the themes in Tall Story originate with Moross. The score takes big breaths and strides, and jazz tinges some of it as well. Despite exciting passages, however, it doesn't hang together all that well. Its nine minutes comes down mainly to small sections joined by a unison fanfare idea in the strings and winds.

However, the Concerto for Flute with string orchestra hangs together very tightly indeed. The first movement, for example, runs to over nine minutes based on two song-like ideas. Mozart again comes to mind, for Moross plays a double game. The "songs" actually comprise little thematic bits, recombined into new "songs," as in Mozart. In both cases, the method effects a highly unified score that seems to be "just singing." Moross's songs have a touch of American pop, however. The score originally called for flute and string quartet – still called a concerto, due to both the prominence and the demands of the flute part – to which Moross added a string bass line in order to increase the performing venues. MHS used to offer the original, along with the Sonata for 2 Pianos and String Quartet, although it's likely long gone from their catalogue. Sprightly and tender by turns, the concerto doesn't strive for Olympus but talks engagingly to us creatures here below. The finale especially reminds me of the spontaneity and vitality of children's games. I don't know about anyone else, but I find such music a better argument for culture and civilization than the storms of the mighty.

Once again, producer Michael Fine has come up with a fascinating and rewarding program off the well-worn path. The performances are good, better than merely professional, with Alexa Still particularly adept at sweet singing when the composer calls for it. Most labels, even when recording unfamiliar repertoire, tend to record the same unfamiliar repertoire, on the likely grounds that it has some sort of track record. Fine mixes less-familiar with largely unknown. In my opinion, his catalogue is one of the most enterprising and lively in the business. And, yes, I bought this disc with my own money.

Copyright © 1998, Steve Schwartz