The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Hovhaness Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

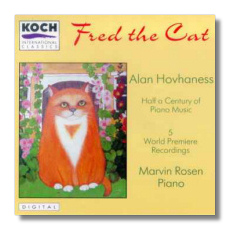

Alan Hovhaness

Piano Works

- Dance Ghazal for Piano, Op. 37

- Achtamar, Op. 64 #1

- Fantasy on an Ossetin Tune for Piano, Op. 85

- Orbit for Piano #2, Op. 102

- Macedonian Mountain Dances for Piano, Op. 144

- Sonata for Piano "Mt Ossipee", Op. 299 #2

- Sonata for Piano "Fred the Cat", Op. 301

- Sonata for Piano "Prospect Hill", Op. 346

- Sonata for Piano "Mt Chocurua", Op. 335

- Slumber Song for Piano, Op. 52 #2

Marvin Rosen, piano

Koch International 3-7195-2 71:21 DDD

There can't be many living composers as prolific as Alan Hovhaness, now in his early 80s. Once upon a time, and not that long ago, Havergal Brian could claim the laurels as the most prolific symphonist since Haydn, with a respectable 32 to his credit (excluding the early and partially lost Fantastic Symphony). But Hovhaness more than overtaken him, with (as of last year) a staggering 67. His opus numbers by now must top the four-hundred mark. Some of this voluminous quantity of music is very good indeed, and some rather treads water. The dilution is obvious in much of this new Koch recording of some of the piano music.

The programme is divided into seven shorter pieces from earlier in Hovhaness' career, followed by four later sonatas. But there isn't much evolution of style and, with one exception (the expansive Sonata, Mt. Chocorua, Op. 335), the sonatas too are essentially collections of miniatures. Much of the music follows the same patterns, structurally (there is a surfeit of ABA forms) and texturally (alternately, walking basses accompanying arabesqued upper lines or long chordal sections). The music remains squarely modal throughout, the harmonic progressions limited in their adventurousness. The thematic material is unabashedly derived from the folk musics of the people from in and around his father's native Armenia, although the opening Dance Ghazal suggests that his Scottish mother might also have been singing in young Alan's ear. But for all its deliberately limited resources, which sometimes makes all the pieces here rather samey, there are passages of unarguable beauty, particularly in some of the extended chordal sections which are veiled in a gently religious mysticism. Walton once said to Hans Keller: "I think it would be a shame if the old triad were done in", and here's Hovhaness showing that there's plenty of juice to be wrung out of basic materials.

Marvin Rosen is a generally reliable guide to these innocent works, though I wonder whether a more aggressive keyboard attack might have brought more of them to life. Still, he has played the works to the composer and discussed the music with him, so one must assume his imprimatur. The recording is slightly close but otherwise unexceptionable.

Copyright © 1993/1996, Martin Anderson