The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Concert Review

Concert Review

The Chicago Symphony in Paris

- Felix Mendelssohn:

- Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, Op. 27

- Claude Debussy:

- La Mer

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky:

- Symphony #4 in F minor, Op. 36

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky:

- The Tempest, Op. 18

- Igor Stravinsky:

- The Firebird, Suite #2 (1919)

- Robert Schumann:

- Symphony #3 in E Flat Major, Op. 97 "Rhenish"

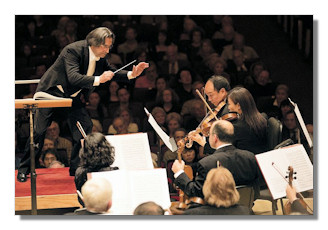

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Riccardo Muti

Paris, Salle Pleyel, 25-26 October 2014

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO) under their Music Director Riccardo Muti finished two magnificent concerts at the Salle Pleyel in Paris. Part of a European tour that took the orchestra from Poland to Austria, by way of Luxemburg, Switzerland and France, these Paris concerts were easily some of the most rewarding classical music acts I attended this year. The choice of repertoire was agreeable, but it was the outstanding quality of the CSO as well as Muti's vision which caused most satisfaction.

73-year old Riccardo Muti appeared in excellent form, completely in command and clearly having a lot of fun while conducting Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Debussy and Stravinsky; scores he knows backwards, of course, but which he continues to bring with freshness and vigor. His profound understanding of the individual styles and sonorities reflected in revelatory readings, brimming with character and emotional content. True, compared to his earlier recordings of some of the works conducted here, he slowed down, sometimes considerably so. But pretty soon you realize that the more restrained tempos are a constructive element rather than a general flaw coming with age. It is Riccardo Muti the maestro of opera, the musician groomed in the theater, whose instinctive sense of drama continually shines through here, and you will be hard pressed to hear more theatrical and colorful performances of symphonic repertoire in a concert-hall. A certain degree of spectacle comes with the bargain, but never did it strike as empty virtuosity or playing to the gallery. The genius of Muti might well be that he can convince us these works were meant to be heard this way.

In the CSO which Muti heads since 2010 he has a stunning formation. Led by Robert Chen, their playing was absolutely extraordinary, whether as an ensemble or in solo parts. There simply wasn't a weak element in the team. The magic was evident from the start with Mendelssohn's Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, allying refinement with sweep. You could argue that Muti's orchestra was rather big for Mendelssohn – or for Schumann the following day – even if there was never a trace of heaviness. In effect, the number of strings never changed during the concerts, but all criticism is silenced by the results Muti coaxed from the CSO. Colors subtly brightened as in a timelapse picture of a sunrise, while the warmth of the Chicago strings gave Mendelssohn's sea a definite Mediterranean glow. Debussy's La Mer, too, was of the clearest water, utterly transparent, revealing every detail of the score. In moderate to slow tempi, yet with a masterful handling of the ebb-and-flow in the outer movements and an unfaltering orchestral balance throughout, it was a riot of color. Climaxes, majestic and often theatrical, were superbly negotiated, topped by the glorious brass and percussion. The impression of warmth and serenity that Muti achieved at the end of the central movement was unforgettable. As we know, Debussy didn't have the Adriatic or the Tyrrhenian Sea in mind when he composed La Mer, but as he himself began working on his marine canvas in Burgundy some liberties are permitted.

Both Tchaikovsky's Fourth Symphony and the little-performed Shakespearean symphonic fantasy The Tempest on the second day benefited from Muti's sense of drama. Muti has always done well in Tchaikovsky. In the symphony the magnificent Chicago brass section, already heard to great effect in Debussy, proved true to its reputation: effortless, precise, brilliantly powerful yet never brutal. Fritz Reiner should have been proud. Muti's nuanced phrasing and flexible chiseling of tempos and dynamics gave Tchaikovsky's restless outpourings a compelling dramatic immediacy. The lyrical quality which is an integral part of Tchaikovsky's style was naturally highlighted, not only in the Andantino in modo di canzone but also in several other passages, as for example in the second theme of the first movement. Cellos, then flutes sang their hearts out, but the real time-suspending moment followed at the Ben sostenuto il tempo precedente notation where the dialoguing strings and winds against a background of soft pounding timpani strokes became almost inaudible in Muti's hands, making the succeeding buildup even more powerful. A bit of extra theatricality was also thrown in for the coda with accentuated long chords. The inner movements were done with plenty of imagination, featuring characterful woodwinds solos and sonorous lower strings. The Finale was thrillingly played, with the CSO in full power, yet without ever sounding strained or ugly.

The unjustly neglected Tempest was a tremendous experience as well. Another evocation of the sea, but one in which, in true Tchaikovsky manner, all expressive and emotional registers are covered. Muti unleashed a terrifying storm after this ravishing opening (which wouldn't be lost on Rimsky-Korsakov) rendered with breathtaking clarity by the strings. The tender love scene between Miranda and Fernando resonated with this molto cantando quality that maestro Muti knows better than anyone else.

Muti readily captured the fairytale atmosphere of Stravinsky's Firebird Suite. Unlike many conductors who seem to consider this score a moment to demonstrate what their orchestra is capable of, Muti never forgot he has foremost a story to tell, even with breaks between the numbers of this suite. Refined, all of contrasting light and obscurity, the appearance of the Firebird was like the burst of Spring. Light and color suddenly pierced through darkness. The growing love between Ivan and the Princess was tenderly evoked, even if at times at a dangerously slow pace, but again providing extra contrast with the Infernal dance with its amazing lower brass. And where can you hear such a beautiful horn at the beginning of the Finale?

Muti has always succeeded his Schumann well (even his 35-years old recordings of his first Symphonies cycle with the Philharmonia can still be counted among the finest) and this traversal of the "Rhenish" was no exception. This is Schumann at the grandest of scales, with a above all a remarkable work on the sonority, now more measured but still pretty energetic in its outer movements, ecstatic in its climaxes, and darkly dramatic in that extraordinary Feierlich fourth movement. The clear-textured playing avoided all heaviness, and needless to say the brass was resplendent – horns in the first movement, trombones in the fourth.

Parisian music lovers know and admire Riccardo Muti – as he has been enjoying a privileged relationship with the Orchestre National for decades. That was obvious each time he entered the hall. Yet there is no doubt that at the end of these concerts they were giving a long standing ovation not just for maestro Muti but also for the CSO, a dream team, a coveted (and rare) musical partnership, and that's a heartening thing to find out in these difficult times for classical music and orchestras in particular. Muti gratified on both occasions with an exhilarating performance of the Overture from Verdi's Nabucco. Pure bliss.

Copyright © 2014, Marc Haegeman