The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Concert Review

Concert Review

Incandescent Mozart and Bruckner

By Marc Haegeman

- Henry Purcell: Funeral Music for Queen Mary

- Wolfgang Mozart: Piano Concerto #20

- Anton Bruckner: Symphony #7

Maria João Pires, piano

London Symphony Orchestra/Bernard Haitink

Paris, Salle Pleyel, 17 June 2012

During their annual teaming up, Bernard Haitink and the London Symphony Orchestra visited Paris for a two-day stint at the Salle Pleyel. On both occasions they were joined by the Portuguese pianist Maria João Pires performing a Mozart concerto. And while Bruckner's Seventh Symphony was offered as the main course for the first, it was Schubert's Ninth which capped the second night.

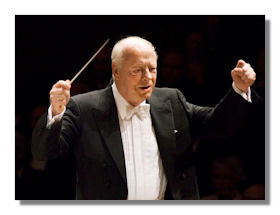

I could only attend the first concert, regrettably, because that proved an utterly delightful experience. The London Symphony Orchestra was in superb form, and that's saying a lot. Moreover, in Mozart, Pires easily warranted her reputation as one of the most compellingly poetic artists at the keyboard today. To guide them all was the incomparable Bernard Haitink, 83 this year but totally belying his venerable age by some of the most refreshing conducting I have heard this year. With Mozart and Bruckner he is of course in his private garden. As a perfect host he continues to reveal moments you never noticed before, no matter how many times you have been there before. Yet he does it in a sober manner. Nothing forced nor twisted, the music seems to flow just naturally from its inspired source, and yet it strikes with a clarity of purpose and a strength of character which keeps resonating long after you leave the hall.

Steven Stucky's arrangement for woodwinds, brass and percussion of Purcell's Funeral Music for Queen Mary, which opened the concert, is already a somewhat outdated curiosity. Commissioned by Esa-Peka Salonen in 1992 for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Stucky took three parts of Purcell's original, added some of his own, veering between minimalism and blatant sound effects. Haitink coaxed precision and clarity from the ensemble. The brass sounded splendid.

Mozart's 20th Piano Concerto in D minor was ravishingly done. The London Symphony appeared in a small formation, with the violins divided left-right, the cellos center left and three double basses to the left. Thankfully there were no attempts to enhance the sound by adding ancient instruments, and, if anything, Haitink proved once again that there is no need for that now common practice. The balance he obtained with modern instruments was carefully judged – the strings didn't drown the woodwinds, the trumpets and horns (per twos) and the timpani added spice to the sound picture instead of turning the piece into a concerto for brass and percussion. As said, all orchestral sections played with tremendous commitment, yet there could be no doubt that Maria João Pires' piano held centre stage even if she did so with disarming modesty and intimacy. Warm and articulate, understated and free of all showiness, Pires subtly balanced between the lyricism and drama that lurks in almost every phrase of the D minor. She upped the tension in the outer movements rather by rhythmical alertness and by keeping a tight dialogue with the orchestra than by overblowing the dynamic range or by sharpening accents. Soloist and conductor were in blessed agreement throughout and the result was nothing short of pure magic: here were two seasoned Mozartians sharing their love for this music and there was no way to resist them.

Pires has a small, almost chamber-music-like sound, yet she fitted perfectly in the carefully woven canvas from Haitink. Her piano sung with touching simplicity in the Romance, but aided by the superb woodwinds she remained fully aware of the latent drama in the middle section. The Beethoven cadenzas acquired plenty of sparkle but remained in style. A magnificent performance.

Anton Bruckner is in safe hands with Bernard Haitink. He recorded the Seventh Symphony no less than three times in the course of his career and although evidently the work has very little secrets left for him, there was nothing routine-like about this performance. Haitink offers a straightforward and clear-headed reading, authoritative without ever becoming stentorian. His grasp of the symphony's fabrics is undeniable. He sets out rather briskly, but he makes the pacing sound natural. Sometimes with an unexpectedly light and graceful touch he marks moments of unearthly beauty, but also dozens of previously unnoticed orchestral details, even if the broad lines retain a clarity essential to the symphony's cohesion. He never lingers longer than necessary yet by holding back the drama he obtains a cumulative effect in the sense that when it finally hits, it hits really hard and often takes you by surprise. As in the Adagio where the superbly negotiated climax with the infamous cymbal crash of the Nowak edition that Haitink performed, acquired a shattering impact. The Scherzo, albeit not exactly taken Sehr schnell as indicated, offered plenty of excitement as well and contrasted not only with a ravishingly delicate trio, but even more with the preceding movements. The final movement, boasting stunning brass chorales, further confirmed Haitink's profound understanding of the symphony's architecture and was deftly molded into a fitting conclusion.

Haitink kept the same basic orchestral setup he had used for Mozart, although it goes without saying the orchestra was now taking every inch of space on the stage. Adding an extra player to each of the brass desks to the original Bruckner orchestra seemed a judicious choice. There were relatively few problems of intonation or of ensemble, even under pressure. Glorious strings and woodwinds played with plenty of character, the brass was powerful when needed, but always kept a convincing balance.

This was by all means an outstanding concert, testament to a magnificent collaboration between conductor, soloist and orchestra.

Copyright © 2012, Marc Haegeman