The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Britten Reviews

Grieg Reviews

Sibelius Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Southern Fire Against Nordic Cool

By Marc Haegeman

- Benjamin Britten: Simple Symphony

- Edvard Grieg: Piano Concerto

- Jean Sibelius: Symphony #1

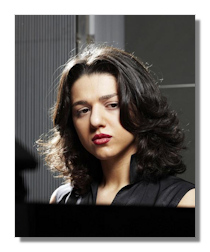

Khatia Buniatishvili, piano

Munich Philharmonic Orchestra/Paavo Järvi

Munich, Philharmonie im Gasteig, 28 April 2012

The German city of Munich boasts no less than three symphony orchestras of international stature. Next to the Bavarian State Orchestra (the former Bavarian Court Orchestra, now the opera ensemble) and the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, it is however the Munich Philharmonic which is considered the true city orchestra. Founded in 1893, in recent times the Munich Philharmonic became mainly associated with Sergiu Celibidache, who was its influential general Music Director from 1979 until his death in 1996, and whose memory remains to this day very much alive – the legendary Romanian maestro even has a (smallish) square named after him next to the concert hall. As of 2012/13 Lorin Maazel will act as the orchestra's Music Director.

I caught the Munich Philharmonic with visiting conductor Paavo Järvi and pianist Khatia Buniatishvili in its magnificent concert hall in the Gasteig Culture Center. The Estonian maestro Paavo Järvi (son of Neeme, older brother of Kristjan) is since September 2010 Music Director of the Orchestre de Paris, but has also been leading to much acclaim the historically-informed German Chamber Philharmonic Bremen for the last eight years, as well as the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra since 2006.

Benjamin Britten's unassuming Simple Symphony may have seemed a somewhat bizarre opener, especially for this orchestra. Yet Järvi had no problem in securing spirited and smartly articulated playing from the Bavarian strings. Actually, he didn't really seem to think of the symphony as that "simple", for with his sweeping dynamics and by spotlighting the emotional content of the "Sentimental Sarabande" he rendered the work a more powerful resonance than usual.

The performance of Edvard Grieg's Piano Concerto was for my money the highlight of this concert thanks to Khatia Buniatishvili who was on fire. The 24-year-young Georgian pianist offered an utterly exciting, unabashedly romantic reading – volatile, commanding in bravura and intense in lyricism. A few weeks earlier I heard Alice Sara Ott's account of the Grieg and found it utterly refreshing. Buniatishvili, although in a very different way, also kicks this old warhorse back to life. With playing of such blazing passion and conviction, including startling attacks, blistering runs, remarkable tempo shifts and bold dynamic shading, she leaves little room for second thoughts about this concerto, no matter how many times you may have heard it. This is a downright gripping piece of music from start to end.

Buniatishvili's piano is brimming with life and energy, as she clearly does herself, sometimes ending a fiery passage with a clear slide or jump on her stool in the direction of the orchestra. The bravura can be mind-blowing but she owns the secret to make it sound like an integral part of the music. There is no denying she is an intelligent artist and while evidently everything has been thought through, her highly responsive and emotive way of playing makes each page of the score sound newly minted and fresh. Hushed passages, like the Piu lento in the 1st movement introduced by the celli, or when the piano is merely accompanying, were time suspending. Buniatishvili's ultra-soft entrances defied belief, as when she shimmered out of the orchestral texture in the dreamy Adagio. Such composure singles her out as a truly remarkable artist. She knows to build up in a few bars an enormous tension which is released with formidable power, as in the 1st movement cadenza.

It was a shame that the orchestral solos, especially some of the woodwinds interventions, weren't more polished. Järvi and Buniatishvili were on the same wavelength regarding tempi, but with the rather dry and hard sound he obtained from the Munich Philharmonic he didn't match her romantic concept, while instrumental finesse seemed to have been the last thing on his mind. It sometimes gave Buniatishvili's color palette a rugged edge, like when the flute introduced the lyrical theme in the last movement or the ensuing passage where that humming cello was far too obtrusive. The final 'halling' dance rhythms however bounced with a rustic joy that was impossible to resist. This is magnificent pianism that demands to be heard.

Järvi returned after the break with a monumental but unsubtle reading of Jean Sibelius's First Symphony. The Finnish composer is not often performed by German orchestras and one can only look back with regret at the Herbert von Karajan days in Berlin. To a certain extent Järvi's dry and unromantic approach served Sibelius better than it did Grieg. He went right for the jugular, giving the music plenty of thrust and attaining thrilling though earsplitting climaxes in the outer movements. Yet by stripping the alternating melodious passages, which are in this youthful symphony still bearing the influence of Tchaikovsky and Dvořák as essential as the grim outbursts, of sentiment and warmth, the emotional range of the Sibelian canvas was seriously reduced. While the Munich Philharmonic enthusiastically followed, refinement and accuracy were a bit too often sacrificed for the sake of vigor. Edgy woodwinds, biting brass and thundering timpani may have produced plenty of visceral thrills, it were nonetheless the strings (antiphonally placed to excellent effect) that made the strongest impression in the melee. Even when hard-pressed they always secured a transparent sound, but it was a shame Järvi denied them warmth.

Copyright © 2012, Marc Haegeman