The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Victoria Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

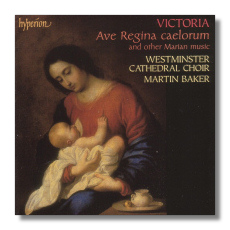

Tomás Luis de Victoria

Marian Music

- Ave Regina caelorum

- Missa Ave Regina caelorum

- Ave Maria

- Dixit Dominus

- Laudate pueri Dominum

- Laudate Dominum omnes gentes

- Laetatus sum

- Nisi dominus

- Magnificat septimi toni

- Ave Maria

Robert Quinney, organ continuo

The Choir of Westminster Cathedral/Martin Baker

Hyperion CDA67479 68m DDD

Also released on Hybrid SACD SACDA67479: Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Summary for the Busy Executive: Slightly disappointing.

A major revolution in western music took place about four hundred years ago. The old system of constructing music based on the so-called "church" modes gave way to the present system of functional harmony. It actually signaled a profound change in more than simply harmony. It transformed the way we perceive musical contrasts and, consequently, musical form. I suspect that almost every listener – even if he doesn't know the technical terminology – can distinguish the major parts of a well-made sonata movement, simply by listening. After all, the key usually changes with each part. We suddenly find ourselves not merely engaged in different musical material, but in a different "home" tonality. The joins between parts became sharper. With the modes, our sense of home never changes. Rather, we may perceive a subtle shift of color as the mode changes.

In other words, barriers have risen between us and music before, say, Purcell or even Monteverdi. We've lost the emotional connection to the modes, other than a sense of archaism and ritual, simply because that's the use put to them by Modern modal composers: Vaughan Williams and Hovhaness, for example. For the high Renaissance, each mode had its own meaning. Because we have written testimony, we know that meaning intellectually, but we probably don't feel it in the same way we feel the meaning of major and minor (probably the remnant of those old modes anyway). Many complain about the "sameness," the "flatness" of the music. On the other hand, I suspect a composer like Josquin would be a bit dismayed at the expressive violence of even Mozart. Furthermore, expressive markings from Renaissance composers tend to be rather rare on the ground. The interpretations of these works have slipped our usual tether, because the composers have told us nothing but notes and rhythm. Even the notes, the pitches, written down are subject to interpretation. I have heard many wildly different realizations of the same mass, to the point where they become almost different pieces.

Performance styles wander all over the map. The preferred scholarly style tends to the careful and, to my taste, the rather dry. On the other hand, I've heard hokum – full of swell pedal and Guiding Light rubatos – that counters the sound of the music. The big problem for an interpreter is how to shape the music, particularly the great masses of the Renaissance – in their aesthetic hierarchy, the equivalent of our symphony. You can't just bull your way through. The best Renaissance composers at least equal our best in skill and subtlety. I've studied this music for over forty years, and I don't claim to have the key. However, I have heard and taken part in revelatory performances.

The Spanish composer and friend of St. Teresa of Avila, Tomás Luis de Victoria, presents fewer problems than many Renaissance composers in that he loves the dramatic. His music brims full with built-in contrast, especially in most of the works here, almost all written for various types of double choir (that is, two distinct choral masses used mainly antiphonally). A conductor still must work out a lot of stuff, but at least Victoria puts some rough guideposts.

Victoria gets contrast and drama mainly by color. He experiments with different combinations of voices. His double choirs are not always equal – eg, SSAT / SATB. Lush chordal passages often break suddenly into quiet, canonic duets. Textures change not particularly whimsically, but almost always because the meaning of the text suggests change. In short, Victoria gives the modern listener more help than many of his contemporaries.

The big work on the disc, the Marian mass Missa Ave maris stella, is a so-called parody mass – that is, a mass based on a previous composition, in this case Victoria's own motet "Ave maris stella." There are two main sections, with the second part in a quick triple-time (analogous to our 6/8), where the text commands us to rejoice – triple-time and joy expressively connected during the Renaissance. Phrases from the motet find their way into the mass, most notably in the Credo's "Incarnatus" section at the words "ex Maria virgine," where we hear the opening phrase of the "Ave maris stella." Phrases based on the triple-time music in the motet pop up during the big praises of the mass &ndash: at the Sanctus's "Hosanna," for example.

Thank St. Cecilia for British choirs, who've done so much to keep this repertoire alive in the first place with first-rate, at times visionary performances. I will say that my favorite performance of a major Victoria work, the Tenebrae Responses conducted by George Malcolm, came out on an Argo LP many years ago. I have no idea whether it ever made it to CD. It was wildly out of style, about as far away from scholarly as you could get (even by the standards of its day), and it packed a hell of a punch. It's probably not what Victoria had in mind, but then again I'm not Victoria. At any rate, brilliant British choirs continue to tackle this stuff with both scholarship and zeal.

Martin Baker has trained his Westminster Cathedral Choir (Catholic, not Anglican) to a high degree of polish. They are rhythmically precise, their diction crackles, their intonation never wavers from dead on, and their tone sounds like the trumpets of angels. Unfortunately, it's the same tone throughout. There's not a wide range of color, except for the textural changes specified by the composer and occasional drops to one-to-a-part singing specified by the conductor. It's okay, but it's not really enough to counter the feeling of sameness that began to creep over me, somewhere in the middle of the mass. To me, this music is the choral equivalent of a string quartet. You simply cannot start a section and continue on automatic. Each phrase probably has its own color. Baker needs to go further, and I'm sure this choir could follow him.

The acoustic is a bit too bright.

Copyright © 2007, Steve Schwartz