The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Dawson Reviews

O'Regan Reviews

Tippett Reviews - Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

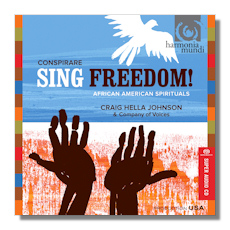

Sing Freedom!

African-American Spirituals

- Craig Hella Johnson:

- Motherless Child

- Soon Ah Will Be Done / I Wanna Die Easy

- Hard Times

- Been in de Storm / Wayfaring Stranger

- Leonard De Paur: A City Called Heaven

- William Levi Dawson:

- Soon-ah Will Be Done

- Ain-a That Good News!

- Moses Hogan:

- Hold On

- Walk Together, Children

- I Got a Home in-a Dat Rock

- David Lang: Oh Graveyard

- Michael Tippett: Five Negro Spirituals - Steal Away

- Wendell Whalum: Lily of the Valley

- Kirby Shaw: Plenty Good Room

- Alice Parker & Robert Shaw: My God Is a Rock

- Robert Kyr: Freedom Song

- Tarik O'Regan: Swing Low, Sweet Chariot

Conspirare Company of Voices/Craig Hella Johnson

Harmonia Mundi HMU807525 72:07 Hybrid Multichannel SACD

Summary for the Busy Executive: Buy this.

I say it often and with conviction: in Western culture, there is no greater song poetry than the African-American spiritual – not Shakespeare, not Blake, not Lorenz Hart, not Johnny Mercer, probably not anybody you will likely mention. The difference between Shakespeare, say, and the anonymous poets of the spirituals lies in the latter's ability to largely bypass the filter of the intellect and lodge directly in the soul or heart. It's the poetry closest to pure music that I know. Furthermore, these unknown poets notice or infer basic things that almost nobody else marked before. St. Matthew asks: "Are not two sparrows sold for a farthing? and one of them shall not fall on the ground without your Father." But the hymnodist tells us "I sing because I'm happy. / I sing because I'm free. / For His eye is on the sparrow, / And I know He watches me." It's that image of a cosmic eye on the smallest, least consequential figure that makes Matthew's message even more powerful. Many artists have noted the grandeur of the Crucifixion and the heroism of Jesus's suffering at Golgotha, but the anonymous slave poet is one of the few who captured the soul of one who was there and trembled. "My Lord, what a morning, / When the stars begin to fall" almost had to be written by people who could see stars at night and indeed lived by what they saw. Do stars actually fall in the sky? I'm a city boy. The only light at early morning I usually notice comes from my TV. I have no notion of whether they appear to fall or not. Telling me that they do, however, connects me with the wonder of the universe.

I admit I'm completely gone over spirituals (and folk poetry in general), to the extent that I own a series of CDs of field recordings of Black churches in the rural South, made before the music industry and radio homogenized and ruined everything. The variety amazes me. Jefferson County, Alabama, may have an individual style, but it by no means stands alone in that distinction. Spirituals mean so much to me (someone who has no religious leaning whatsoever, not even to atheism) that I want to protect them, and arrangements become very important to me. I don't like gimmicks. I don't particularly care for genteel notions of art. Spirituals appeal to me mainly through their directness and vigor, even the slow ones, which emerge more clearly the closer you get to the people who sang them, not as art but as genuine worship. The solo "art song" spiritual from the early part of the last century seemed to me mostly a failure, with the exceptions of Henry Thacker Burleigh and Hall Johnson, but I may feel that way because of the arty manner of the singers, rather than of the music.

My favorite spiritual arrangements tend to be choral. Here, one notes several approaches. There's what I'd call a classic approach. It tends to trust the power of the tune and the implied harmony. Arrangers William Levi Dawson, Wendell Whalum, Undine S. Moore, H. T. Burleigh, Eva Jessye, and Hall Johnson typify this viewpoint. One also finds the back-to-basics strategy of a writer like Joseph Jennings, less concerned with academic, written composition techniques and returning to orally-transmitted "head" arrangements. Probably the most ubiquitous approach is a "concert" one, exemplified by the Alice Parker/Robert Shaw collaboration as well as by Salli Terri, and many others. Finally, we get "meta-spirituals," where the basic piece provides a jumping-off point for a poetic re-imagining and, in some cases, a transformation of the African-American tradition.

Of the arrangers here, Dawson is represented by two mainstays: "Ain'-a That Good News" and "Soon-ah Will Be Done." I should note that Johnson chooses Dawson's revisions, created at a distance of decades from their initial inspiration – more elaborate and, to my mind, less effective than the incisive originals. One marks this tradition carried on in Kirby Shaw's infectious "Plenty Good Room" and Hall Johnson alumnus Leonard De Paur's yearning "A City Called Heaven" neither one guilty of wasted note. We hear Parker-Shaw's "My God Is a Rock," an extremely sophisticated work that nevertheless aims to recreate the raw power of the folk hymn and pulls it off.

Craig Hella Johnson has contributed some of the most intense settings on this disc. He penetrates the essence of these masterpieces mainly by trusting the tune and the words to speak. They hardly seem arranged at all, which of course they are, and I can't think of anything better to say. One "fingerprint" of Johnson's arranging is his gift for seeing connections among divergent things. This capacity informs his cncert programming as well as his composing. "Soon Ah Will Be Done" meshes with "I Wanna Die Easy," not only textually, but musically to such an extent that it strikes me like two soliloquies on different sides of town that magically meet up as a conversation. I'd say the same for his "Been in de Storm / Wayfaring Stranger." "Hard Trials" adds a lovely Coplandian piano part to a choir and a heartrending soprano soloist. The writer lived her entire life as a slave and described what she felt being sold not once, but twice.

Oh de day dey had her on de auction block,

Been poked and pushed and tried,

Was de day her heart completely broke,

Was de day her heart done died.

Now ain't them hard trials, great tribulation?

…

Incidentally, I came of age in the Sixties, during the Black civil rights struggle. I heard Martin Luther King speak live four times (three of them at my college), and I remember vividly each occasion. The "de's" and "dey's" normally bug the hell out of me, since they remind me of patronizing white minstrelsy. "Gwine" is a special peeve, since I've lived in the South for over thirty years without hearing anybody of any class or color actually say it, except ironically. "Chirren," "axt", and "go'n'" yes; "gwine" never. But, of course, you look at these things on the page and, if you're anything like me, you hear in your head Freeman Gosden and Charles Correll and similar horrors. It takes strong imaginations to transcend strong expectations. English spelling lacks aural precision. In the real (as opposed to stage) dialects that come closest, the "t" sound is less distinct or softer or more voiced than standard, but you still recognize it as some sort of "t." The "e" of "de" is really a high palatal, nearly dental schwa, something like an unstressed "ih." Conspirare choir and soloists lift the curse from these things and sound like real human beings, rather than aural cartoons.

In a crowd of imaginative arrangers, conductor and musical force Moses Hogan stands out – probably the greatest of his time. He edited the Oxford Book of Spirituals and died way too young of a brain tumor. I don't know how many spirituals he set, but almost all of them became instant choral classics. He worked with imagination and flexibility, never falling into shtick and always looking to the spiritual itself to dictate the setting. His arrangements range from simple ones for amateurs and churches to those that challenge even elite groups like Conspirare. Hogan also had a career as a concert pianist, which sometimes influenced his writing, particularly his chord spacings, and he had a phenomenal harmonic ear, akin to the greatest jazz players. Check out his arrangement of "Abide with Me" for some ear-stretchers. The three pieces here give you some idea of his range.

"Hold On" recreates an über-gospel choir with a trio of super-sopranos rising above a roiling choral mass. It taxes the best of choirs just to get through it. On the other hand, "Walk Together, Children" is deceptively simple. Merely a good choir could perform it without serious mishap, but Hogan also asks of the singers to swing in a slow tempo, difficult for most. "I Got a Home in-a Dat Rock" knocked me for a loop the first time I heard it. In many ways, it's the most straightforward of this threesome. It surprised me in that the part-writing and harmony lies remarkably close to an arrangement of the spiritual by Melvin Butler, as far as I know never published and indeed never performed by anybody other than the Oberlin College Choir. I went to school with Butler and sang with him in the choir when he came up with his version. We premiered it. I have no idea whether any other Oberlin choir performed it. However, Hogan, Butler, and I are fellow Oberlin alums. Had Hogan heard it (he graduated at least ten years after Butler and I)? I have no idea. There's enough of Hogan himself in his arrangement to quash any suggestion of conscious copying. Perhaps unconscious memories of Butler's earlier job lingered in Hogan's head.

We now come to the "meta" arrangements. Most probably know Michael Tippett's "Steal Away" best. Created for the oratorio A Child of Our Time, Tippett wanted to find a modern equivalent to the chorales in Bach's Passions as a universal commentary on stages of the action and picked the Black spiritual. In the process of universalizing, Tippett got rid of any hint of exoticism, and to a Briton of the Forties, African-American music would count as something exotic. Unique musical results ensued.

Johnson has championed both Robert Kyr and Tarik O'Regan to the extent of commissioning substantial work from them. O'Regan's "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" creates an atmosphere of "spiritual ether," music of the spheres, through which flow the cells, the RNA, of every spiritual including, subtly, the basic material of "Swing Low." Robert Kyr's "Freedom Song" undoubtedly has made my personal all-time jukebox. Here, we get nearly the raw African sound, as found on the Seaward Islands off the South Carolina coast – the Gullah-Geechee tradition. Interestingly enough, you can find a precedent for Kyr in the hurricane prayer from George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess. Gershwin, of course, had heard the music on the islands as part of his research for the opera. The Kyr sets individual phrases against a steady, subtly syncopated beat. As the piece progresses, single voices enter almost at will with their own material, as members of the congregation comment on the "big sing," raising the already considerable energy to higher peaks until the end. For some reason, it reminds me a bit of Veljo Tormis's "Curse Upon Iron," also part of the Conspirare repertoire. Did I mention I love this piece?

For my money, no group in North America (and precious few world-wide) equal or surpass Conspirare. They turn the difficult works like the Hogan "Hold On," the Kyr, and the O'Regan into tours de force. Sharp rhythm, terrific color, diction, and intonation, of course, but they also communicate like nobody's business. For a choir this skilled, the simpler works pose just as tricky problems, because they offer the temptation of easing up or, worse, slacking off.

The soloists are universally wonderful and vocally various. I'll call the roll of the specially memorable. Melissa Givens has a voice you imagine coming from the goddess Erda and gives "Motherless Child" even more depth than it has all on its own. Matt Alber in "Soon Ah Will Be Done" has a "folk voice" and fearless control. I like to think the original singers sounded this good. Abigail H. Lennox matches him in "I Wanna Die Easy." Nicole Greenidge, with a voice sweet as fresh water, tears my heart out over her hard trials. She and her costars in the powerhouse "Hold On" trio, Stefanie Moore and Gitanjali Mathur, blow the roof off. In the "Been in the Storm / Wayfaring Stranger" duet, Wendy Bloom and Sonja Tengblad will awe you not only with the purity of their voices, but with their sure dramatic instincts as well. In the David Lang, the quartet of Nina Revering, Carr Hornbuckle, Cameron Beauchamp, and Matt Tresler powerfully evoke disembodied wraiths bound to and crying through the graveyard. Tracy Jacob Shirk sings the Tippett better than anyone else I've ever heard (mainly because he doesn't sound like a British operatic tenor who's found himself in a country church) and Julie Keim as good or better than anybody other than Janet Baker. Charles Wesley Evans has a bass that the Mt. Rushmore quartet would have been proud to claim for their own, as he preaches the Gospel in a weary land. David Farwig puts his ringing baritone to "Home in-a Dat Rock" and "Freedom Song." His colleague in "Freedom Song," mezzo Keely Rhodes matches him ring for ring in the stratosphere and has an impressive lower range as well.

I can think of a line of great Spiritual albums: the Smithsonian Institute's Wade in the Water, Marian Anderson's solo recital, the Robert Shaw Chorale's Deep River and I'm Gonna Sing, and Joseph Jennings's Chanticleer Where the Sun Will Never Go Down. This album – along with Johnson and Conspirare's Company of Voices – belongs right in there. Classic. Buy it. Buy it. Buy it.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz