The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Distler Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

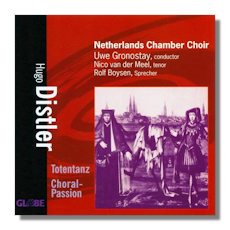

Hugo Distler

Sacred Choral Music

- Totentanz, Op. 12 #2

- Choral-Passion, Op. 7

Netherlands Chamber Choir/Uwe Gronostay

Globe GLO5175 77:21

Summary for the Busy Executive: Altars carved in wood.

Hugo Distler (1908-42) studied piano and organ. Composition more or less came along with his organ studies. He discovered he had a talent for it and published his first two opus numbers while still a student. He became caught up in both the 20th-century revival of the early German Baroque and in its concomitant religious movement. He became the organist at the Lübeck Jakobikirche, where he would compose most of his sacred music. He also received an appointment to the faculty of the Lübeck Conservatory.

When the Nazis came to power, some Protestants hoped that the party would favor the church. One of these, Distler joined the party. However, the Nazis' hostility to religion and therefore to sacred music became increasingly clear. As the Nazis began to harass and clamp down, Distler moved from faculty to faculty. Furthermore, many of his friends had tried to resist the Nazis and were arrested. The Protestants split into the pro-Nazi toadies (the German Christian Movement, which among other things decided to rid Christianity of "foreign" influences like the Old Testament – obviously Jewish) and the so-called "Recognized Church," which opposed Nazi racial policies. The Nazis confiscated church funds and arrested pastors, at the least forbidding them to preach. Some perished in the camps. Also, the threat of recruitment into the army and to the Eastern Front constantly hung over Distler's head. He found protection in high circles for a time but no respite from being called up. He got his wife and children out of Germany, while he remained behind. The terror and brutality of the Nazis depressed him. After one final attempt to draft him, he committed suicide. Ironically, another exemption came through shortly thereafter.

Musically, Distler owes much to two predecessors: Heinrich Schuetz for the forms of particularly his large-scale works and Paul Hindemith (especially the Lieder nach alten Texten – songs on old texts) for harmony and counterpoint, although Distler has distinctive contrapuntal traits of his own. Rhythmically, he typically ignores the bar line so that phrases don't necessarily correspond to measures (or each part has different measures) or stress the usual beats of the stated time signatures. This results in a very flexible, independent musical line. Different voices often don't stress at the same time. These attributes make Distler's scores difficult for most choirs, and although his importance to Modern choral music is great, his body of work seems to scare performers off. The sound is cool, even remote, although Distler does have his tender moments, usually when he depicts innocence.

The Totentanz (dance of death) comes from roughly 1936. The Dance of Death is actually a literary and painting genre, portraying the inevitable power of death over all humanity, often with admonitions to righteousness so you can enter heaven. Perhaps its most famous modern depiction is Bergman's Seventh Seal, although there, of course, Death, like modern-day humans in general, has no idea whether heaven exists. One can also cite the frescoes of the Lübeck Marienkirche (destroyed by bombs during World War II) and a series of 15th-century woodcuts. Besides choir, the forces include several speakers, one representing Death, the others his various victims: emperor, bishop, nobleman, physician, merchant, knight, sailor, hermit, peasant, maiden, old man, and child. The work sounds bone-simple, but as one who's actually sung it, I can tell you it can give a choir fits.

The Choral-Passion of 1933 depicts Christ's Passion from texts drawn from the four Gospels in Luther's translation. Structurally, it owes almost everything to Heinrich Schuetz's larger works, like the St. Matthew Passion (1666), for example. Two male soloists, one taking the role of Jesus and the other the Evangelist, sing unaccompanied recitative which advances the familiar story. The choir provides commentary or deepens the emotional points in a series of chorales and also take on the traditional dramatic role of the turbam (crowd), usually playing against Jesus. The score's sparseness contributes to a hypnotic ritual quality, something very close to the best religious folk art.

Neither of these works is easy. Keeping pitch in a sophisticated harmonic environment for half an hour at a time simply poses one difficulty of many, although recording obviously eases the problem. Uwe Gronostay has earned an enviable reputation in difficult Modern choral repertoire, and the Nederlands Kammerkor is simply one of the world's greatest choral ensembles, with an ensemble sound uniform and dead-on in pitch. The choral tone is a German – ie, "woody" and a bit remote – but that suits this music down to the ground. It results in Distler beautifully done, one of the best recordings ever of either work.

Copyright © 2010, Steve Schwartz.