The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

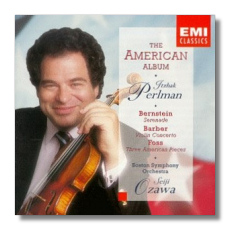

The American Album

- Leonard Bernstein: Serenade (after Plato's "Symposium")

- Samuel Barber: Violin Concerto Op. 14

- Lukas Foss: Three American Pieces

Itzhak Perlman, violin

Boston Symphony Orchestra/Seiji Ozawa

EMI Classics 55360-2

The life of a violin superstar has its problems. When you've already recorded the Beethoven, Brahms, Mendelssohn, Vivaldi, Bach, Mozart, Tchaikovsky, Elgar, and Bruch, how do you make another best-selling CD, particularly when the young Turks nipping at your heels can offer their versions of these pieces with the major selling point of novelty? I suppose you can record the Top Ten all over again, although with little artistic reason. Gimmicks – "crossover," "tributes" to jazz or klezmer or long-dead violinists, soundtracks – work occasionally, but eventually you've got to bite the bullet and learn new repertoire. With his concert schedule, when does Perlman find the time to practice?

Make no mistake, I think Perlman a superb violinist, a musician who deserves almost all the praise he gets. My questions are genuine. He has obviously put in more hours on his Tchaikovsky than on his Bernstein. In fact, I'd go so far to contend he's probably put in the same amount of effort into the repertory on this disc as anyone else. So why listen to Perlman's interpretation of the Serenade as opposed to Kremer's, Francescatti's, or McDuffie's? What recommends his Barber, as opposed to Shaham's, Stern's, Oliveira's, or Ricci's? I suspect less of a difference among the violinists and more among the conductors, orchestras, and ensemble between soloist and orchestra.

Many composers lurk in Bernstein's music. Hindemith crops up in the Clarinet Sonata. Copland's jazz period informs On the Town. Bernstein sends a valentine to Viennese operetta in Candide. Trouble in Tahiti is one of Marc Blitzstein's better works. Tchaikovsky wafts through West Side Story, and Appalachian Spring burbles up occasionally in the Symphony #3 "Kaddish." I mean no disparagement. In fact, it amazes me that Bernstein can include so much so obviously and still come up with something unmistakably his. Eliot was right: immature poets imitate; mature poets steal.

The Serenade is Bernstein's Stravinsky piece, and Perlman carries impeccable Stravinsky credentials. In fact, after conducting Perlman in the Violin Concerto, Stravinsky confided that he would have liked to have "Perlman play in every subsequent concert in which I appear." The violinist also put out a wonderful recording of the Suite italienne and the Duo Concertant in the mid-70s, not transferred to CD, as far as I know, unless it's made it to Perlman's kitchen-sink EMI set. My favorite recording remains Kremer and the Israel Philharmonic conducted by Bernstein (DGG 423 583-2), but the edge comes from Bernstein, who turns in a super-charged performance. Still Ozawa and the Boston don't lag far behind, and Perlman comes in with a surprisingly committed performance, particularly in the "Agathon" Adagio. Furthermore, he wins over Kremer with a slightly warmer, fuller tone. Kremer, however, swings better in the jazzier parts of the score. Still, both performances grab your attention from the beginning, and I'm no Ozawa groupie. McDuffie and Slatkin on EMI take a more restrained approach, as if Bernstein really were Stravinsky the neo-classicist, but who wants restraint from Bernstein?

The Barber violin concerto shows signs of becoming the Mendelssohn Concerto of our century. After years of neglect, everyone and their contracted conductor is rushing to record it. I've even heard 12-year- olds sail through this work. You would think this work made for Perlman's sweet singing, but oddly enough both Ozawa and Perlman have trouble finding the groove of the music. An air of self-consciousness pervades this account, as if they are performing neo-Romantic music instead of music. It would surprise me to learn that Barber thought of himself as a neo-Romantic. Shaham plays with more ardor, as does Isaac Stern in what remains for me the definitive performance – the one I imprinted on – with Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, as far as I know never transferred to CD. Bernstein had no especial love for Barber's music (and the regard, I gather, was mutual), but he did understand how a composer arrived at a score. His performance burns into the wood.

I suppose most people think of Lukas Foss – if they do so at all – as the good Lukas Foss and his evil twin, Lukas Foss. Up until, and possibly through, his Time Cycle in the early 60s, he was a fair-haired darling of American music, firmly in our neo-classic symphonic tradition, with raves from everyone from Copland and Hindemith to Stravinsky. Why not? The music deserves it – The Prairie, oboe concerto, the two piano concerti, The Jumping Frog of Calaveras County, the string quartet, Song of Songs, Parable of Death – impressive works in anyone's catalogue, brilliant and supremely musical. During the 60s, however, he began to take less-travelled roads – group improvisation, aleatorics, minimalism, his own experimentalism, lately post-modernism – always in his own way. Few composers have followed up his experiments. I'm not always thrilled by what he composes, but I have to admit its imagination and sheer musicality.

The Three American Pieces is Foss's recent orchestration of his Three Early Pieces for violin and piano, written while in his young twenties. Foss admits the influence of Copland Americana, but the matter really isn't so simple. To me, it's a European sensibility coming upon the energy of American folk music. Believe me, you won't mistake these works for Copland. The rhythm doesn't quite tap true, for one thing. Nevertheless, these are extremely attractive works, often evoking the country fiddle, particularly in the last movement, with its hints of "Little Cindy." Not terrific challenges to interpretation, but I'm sure as hell glad Perlman chose to record it. Now all we need are the two Piston violin concerti and perhaps the one by William Bergsma.

The sound is very bright and the recording levels extremely high. Make sure you don't blow out your speakers.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz