The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

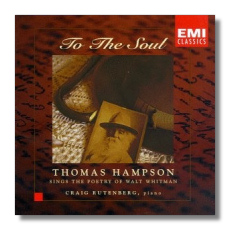

To the Soul

Songs on the Poetry of Walt Whitman

- Ned Rorem:

- As Adam Early in the Morning

- Sometimes with One I Love

- That Shadow, My Likeness

- Look Down Fair Moon

- Frank Bridge: The Last Invocation

- Charles Villiers Stanford: To the Soul

- Ralph Vaughan Williams:

- A Clear Midnight

- Joy, shipmate, joy

- Robert Strassburg: Prayer of Columbus

- Ernst Bacon: One Thought Ever at the Fore

- Philip Dalmas: As I Watch'd the Ploughman Ploughing

- Paul Hindemith: English Song #8 "Sing On There In The Swamp"

- Charles Naginski: Look Down Fair Moon

- William H. Neidlinger: Memories of Lincoln

- Harry T. Burleigh: Ethiopia Saluting the Colors

- Hermann Finck: In the Shadows

- Charles Ives: Walt Whitman

- Gerald Busby: Behold This Swarthy Face

- Elinor Remick Warren: We Two

- Craig Urquhart: Among the Multitude

- Michael Tilson Thomas: We Two Boys Together Clinging

- Leonard Bernstein: To What You Said

Thomas Hampson, baritone

Craig Rutenberg, piano

EMI 55028 74:49

Summary for the Busy Executive: A mixed bag, O Soul!

In the latter quarter of the Nineteenth Century, Whitman's poems broke into general public consciousness. With Whitman's distrust of Europe, it must have at least struck him as ironic that his first widespread critical acceptance took place in England, among the Pre-Raphaelites, Aesthetes, and Decadents (particularly Swinburne, Rosetti, and Symonds) rather than from his own countrymen. Americans in general first learned to pick up Whitman and read from their English cousins. Whitman quickly became more than a poet – a symbol for several simultaneous things: the New World's poetic Declaration of Independence from European forms, largely French and Italian, and British poetic diction. It's unlikely, for example, that anyone used the word "yawp" in a serious poem before Whitman. Emerson and Thoreau had freed the essay from its belle-lettristic confines. Melville had given the novel a range and metaphysical power, as well as a sense of a huge natural landscape, beyond even that of Dickens. Emily Dickinson introduced the sound of American common sense into lyric poetry, a sound that echoed in such diverse writers as Pound, Stein, Cummings, and Williams. Mark Twain did the same for prose and shifted the American culture firmly from Eurocentrism to Americentrism. If Washington Irving went to Europe to find the center of the cultural universe in his travel essays and tales, Mark Twain took the center of the universe with him wherever he went.

Whitman, on the other hand, has always had more constituencies than any other American writer. Indeed, the poet Roethke declared that every American poet sooner or later has to make his peace with Whitman. He has passed from the Decadents to the British and American Socialists to macho American jingoists to various gay constituencies and advocates of sexual liberation. His sub-collection, Calamus, has been raided for texts by the latter. Along with Shakespeare, Housman, and Blake, Whitman is probably the poet in English most often set.

The program on this CD interests me mainly for its range of musical styles and for its demonstration of how the notion of song has changed. Songs in English have been mainly rhymed and metered, especially in the Common Time ("As I was going to St. Ives, / I met a man with forty wives") and the Common Meter ("How doth the busy little bee / Improve each shining hour?") of hymns and folk songs. Whitman's poetry explodes almost all hope in this sort of musical solution. The only poem he ever wrote that comes close to the traditional song is "O Captain! My Captain!" – not one of his best, unfortunately, but at one time his most popular, especially in U.S. schoolrooms. A strenuous attempt was made to smooth Whitman out – "the good, gray poet" – and we see its reflection in many early settings. One of the most grotesque is William H. Neidlinger's "Memories of Lincoln" from 1920, which glues parts of "Beat! beat! drums," "When lilacs last," and "O Captain!" in a campy composite. One suspects that we get this misshapen mess because Neidlinger can't handle Whitman's complex rhythms, which blow the normal song-writing strategies of the time all to hell. Neidlinger keeps trying to find the conventional equivalent. Thus, he begins his "Beat! beat! drums!" with a kin to "On the Road to Mandalay" and, when he gets to "When lilacs last," slips into "My Buddy." The same sort of thing defeats Henry Thacker Burleigh's "Ethiopia Saluting the Colors" (1915), although Burleigh (a pupil of Dvořák) does much better than Neidlinger and, taking off from the poet's reference to Sherman, manages to weave in strands of "Marching through Georgia." Elinor Warren ("We Two," 1947) and Robert Strassburg ("A Prayer of Columbus," 1993, radically abridged – almost always a bad sign) resort to hokey repetitions solely in order to get the phrasing "to come out right," ie, according to the lights of the conventional song. Indeed, it's difficult for me to believe Warren studied with Nadia Boulanger. Her song sounds like it could have been composed by Oley Speaks for Lawrence Tibbett – whom, incidentally, she accompanied at the piano for many years.

Stanford's "To the Soul" (1906-08, the same text his pupil Vaughan Williams set for Toward the Unknown Region, 1905-1907) takes a harder, Brahmsian route; he ingeniously finds a musical structure, to some extent distinct from the poetic one, but not at cross-purposes. We can say the same for Ernst Bacon's later "One thought ever at the fore" (1930) and Bernstein's "To what you said," a highpoint from his magnificent late work Songfest (1976), a work filled with highpoints. Both essentially begin a song in the instruments, which the voice decorates and comments upon.

One of the more interesting settings, though not entirely successful, is Philip Dalmas's "As I watch'd the ploughman ploughing," composed sometime before the composer's death in 1928. Dalmas intuits that perhaps Whitman's new poetic expression suggests a new musical expression. He doesn't find one, but he stretches the traditional pretty far, with mostly the voice and piano insisting on their own pedal points – essentially, the singer becomes, until just before the end, "Johnny One-Note." It's a song of great risk, which to a great extent comes off.

With the modern era, Whitman setting comes into its own. The asymmetrical phrase, practically a hallmark of Modernism, handles Whitman's rhythms admirably. Frank Bridge's "The Last Invocation" (1919) sensitively ties the poem together through a piano figure, rather than through the vocal part. Vaughan Williams' "A Clear Midnight" and "Joy, shipmate, joy!" (both 1925) revel in and emphasize the irregularities of Whitman's rhythms – the first in the way of a folk singer humming to himself, the second a more straightforward Modernism. Into this last category we can also put Ives' "Walt Whitman," the only time our musical Whitman ever set the poet. Typically, Ives puts us through a complex experience – part pure music, part cultural and metaphysical comment – in less than a minute. Michael Tilson Thomas contributes a beautiful Coplandsmann version of "We two boys together clinging" (1993). It doesn't make you forget Copland, but, on the other hand, Copland would probably have loved to have written a song this good.

The American popular song has also contributed to breaking down old poetic rhythms, as anyone can tell who takes the trouble to scan a Lorenz Hart lyric. Kurt Weill's "Dirge for Two Veterans" (1942-47) could have come out of Street Scene. One hears the same kind of pop-rhythm shuffle in Charles Naginski's "Look down fair moon" (1940) as well as a startling resemblance to Gerald Finzi's (probably later) "Come away, death." It's unlikely, however, that Finzi ever heard the earlier song.

My favorite songs on the album include the Vaughan Williams, the Ives, the Bernstein, the Bacon, the Thomas, and Hindemith's "Sing on there in the swamp" (1944). If you know Hindemith's setting in When lilacs last in the dooryard bloom'd, this ain't it. Completely different, it's yet another perfect setting of this text. The most amazing songs, as a group, on the CD belong to Ned Rorem. None of them seem "worked" at all – each, rather, a spontaneous musical expression of its poem, words and music cling together so intimately. I can't see a point in dissecting them, since I'll never learn how Rorem did it in the first place.

As for Hampson's performances, to me this is one of his best CDs. Sometimes he can ruin a song from trying too hard for an over-fussy, even corny Interpretation, but not here. The songs serve the singer less than the singer serves the songs (try saying that fast three times), and it's all to the good. His virtues – a long, seamless vocal line, impeccable American diction, an ability to find the right dramatic persona for the song, and direct communication with the listener – shine. He does well even by the weaker songs. Even the Warren and the Neidlinger come off with less of a curse because Hampson has taken the trouble to show them in their best light and doesn't condescend. Rutenberg matches him. His extended solos in the Thomas and Bernstein are exquisite.

Now to complain. Four minutes of this CD Hampson gives over to spoken recital of certain Whitman poems. I have no idea why he does this. He's a good reader, but a great one. He does no better than you would if you read these poems to yourself and certainly reveals nothing new about them. I mean, it's not like we're listening to Olivier or Rip Torn. On the other hand, this still leaves over seventy minutes of music.

Hampson, collaborating with Carla Maria Verdino-Süllwold, also tried to provide scholarly liner notes, but typos and other editorial slips sink that boat. For example, they make much of Whitman's early lack of musical sophistication because he uses the word "band" to mean an orchestra. This is a common nineteenth-century usage, persisting even in such musical yokels as Ernest Newman, George Grove, Donald Tovey, and George Bernard Shaw (sarcasm mode off). Just below this assertion, they include an extensive Whitman quote which uses the word "orchestra" more than once ("band" is nowhere in sight). This could very well be a later excerpt, but as it stands, it just confuses people. At one point Ernst Bacon is lumped with Hindemith as "transplanted Europeans." At another, the notes state that he was "born and educated in Chicago."

There's also a track goof. The Hindemith appears at the tail of the Strassburg track 8 as well on its own track 11. Somebody just wasn't paying attention.

But these things shouldn't stand in the way of enjoying a fine recital.

Copyright © 2002, Steve Schwartz