The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Villa-Lôbos Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

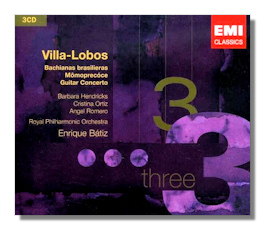

Heitor Villa-Lôbos

Complete Bachianas brasilieras

- Bachianas brasilieras 1

- #1 for 8 Cellos

- #2 for Orchestra

- #3 for Piano & Orchestra

- #4 for Orchestra

- #5 for Soprano & 8 Cellos

- #6 for Flute & Bassoon

- #7 for Orchestra

- #8 for Orchestra

- #9 for Chorus & String Orchestra

- Mômoprecóce 2

- Guitar Concerto 3

1 Jorge Federico Osorio, piano

1 Barbara Hendricks, soprano

1 Lisa Hansen, flute

1 Susan Bell, bassoon

2 Cristina Ortiz, piano

3 Angel Romero, guitar

1 Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Enrique Bátiz

2 New Philharmonia/Vladimir Ashkenazy

3 London Philharmonic Orchestra/Jesús López-Cobos

EMI 500843 207:03 3CDs

Summary for the Busy Executive: Boxy sound and, for the most part, mediocre performances.

Heitor Villa-Lôbos overflowed with music. His output is large, diverse, and scattered. The series of nine dance suites, – Bachianas brasilieras, composed over a period of roughly fifteen years – provides one of the few focal points in his catalogue. They have received, of all his works, the greatest number of recordings (especially #5), and they brim over with exciting, colorful music. Villa-Lôbos produced a set of symphonies as well, but unlike the Bachianas or the string quartets, they do not constitute a central or important part of his achievement.

Villa-Lôbos mostly taught himself to compose. To the end of his days, he retained the exuberance, the eccentricity, and the supreme confidence of the autodidact. About to travel for the first time to Paris, then the hub of musical Modernism, he replied to friends' inquiries about whom he would study with, by asserting, "They will learn from me." His great achievement as a composer lay in his ability not only to synthesize various currents of Modern music into his thoughts, but also to create some of those currents. I believe it safe to say that nobody before Villa-Lôbos got the rhythm and melos of South America into their music. Even Darius Milhaud (Saudades do Brasil, for example) comes later, toward the end of World War I. Villa-Lôbos had already been writing for years.

Some confusion hangs over the Bachianas brasilieras, not least over its name. I understand that even Brazilians find the title odd, and the composer himself spoke a little vaguely about it. I would translate it (not knowing any Portuguese) as "Bach-like musings from a Brazilian perspective." They're not imitations of Bach. They're not even like Stravinsky's appropriations in, say, the "Dumbarton Oaks" Concerto, or Vaughan Williams in the Concerto accademico. They don't use a specific work by Bach as a model, nor do they take decorative elements. Instead, Villa-Lôbos freely adapts Baroque procedures to his own music and focuses on the latter.

Different Bachianas specify different forces: #1, an ensemble of at least 8 cellos; #2, 4, 7, and 8, full orchestra; #3, piano and orchestra; #5, soprano and a cello ensemble; #6, solo flute and bassoon; #9, wordless chorus, usually done (as here) with string orchestra.

The main advantage of this set lies in the very fact of collection. I wish the performances were better. The Royal Phil celli have difficulty even keeping in tune in #1, and the rest of the performances are generally pokey. Barbara Hendricks tries valiantly to save #5, but again, the ensemble does her in. Flutist Lisa Hansen and bassoonist Susan Bell give a lively performance of #6 – head and shoulders above the accounts of the other Bachianas. However, Bis BIS-1830/2 is still available, and miles beyond the Bátiz. It also contains the complete Chôros cycle, and everything comes in its original version, including the ninth Bachiana for chorus. You can certainly find individual readings (at least 50 for #5 alone). I'm partial to Michael Tilson Thomas and the New World Symphony's selection on RCA68538 (#4, 5 with Renée Fleming, 7, 9 for strings, and Chôros #10).

That's two of the three discs. The third disc tells a slightly different story: different orchestras, different conductors, different soloists. In 1929, Villa-Lôbos rewrote a suite of piano pieces based on Brazilian children's songs as Mômoprecóce, a fantasy for piano and orchestra. It's colorful, although a bit loose. Cristina Ortiz plays with a curious detachment and Vladimir Ashkenazy's New Philharmonia are a bit spongy on the attacks, precisely what the music doesn't need. Of the ten designated concerti I know about (5 for piano, 2 for cello, 1 each for harp and harmonica), the one for guitar (1951) has won the greatest exposure. A guitarist himself (as well as a cellist and clarinetist), Villa-Lôbos of course had produced many solo classics for the instrument. He wrote the concerto for Segovia, who complained that it wasn't virtuosic enough, and so he added an extended tricky cadenza as a bridge to the final movement. I like the work a lot. The opening contrasts a dance of great rhythmic incisiveness with sweetly nostalgic song. The second movement concentrates mainly on the lyrical qualities of the guitar. The finale goes from one dance to another. Again, the orchestra and conductor splooge their attacks, but Angel Romero puts them to shame rhythmically with articulation so sharp, I wonder he didn't cut himself. This undoubtedly ranks as the best performance on the three discs, but it's also available on a single CD, along with Ortiz's Mômoprecóce. I think that pretty much scuttles the set.

Copyright © 2011, Steve Schwartz