The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- F.J. Haydn Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

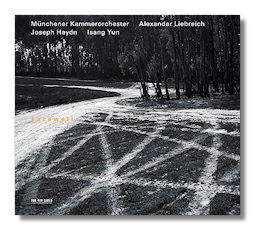

Franz Joseph Haydn

Symphonies

- Symphony #39 in G minor

- Symphony #45 in F Sharp minor, "Farewell"

- Isang Yun: Chamber Symphony I

Munich Chamber Orchestra/Alexander Liebreich

ECM New Series 2029 (4766188) DDD 69:56

ECM New Series has a reputation for innovative programming. I wouldn't expect Telarc or Sony Classical, for example, to include music by Joseph Haydn and Korean-born composer Isang Yun on the same CD. What could be the reason for this? These three works all were recorded at the same time (May 2007), so their juxtaposition was not an afterthought. Perhaps they even appeared on the same concert program. One turns to the booklet note by Paul Griffiths for an explanation. It's a very good booklet note, but even Griffiths is unable to come up with a truly credible explanation, although he does wave his arms about in a vain effort to connect Haydn and Yun. For the real explanation, you need to read conductor Alexander Liebreich's bio at the end of the booklet. It turns out that Liebreich simply has had connections with Yun's family, has worked in Korea, and feels a commitment to advancing both modern music and music from earlier eras. Fair enough!

The two Haydn symphonies are from his "Sturm und Drang" period, whose approximate dates are 1765 to 1772. Griffiths rightly cautions that we shouldn't necessarily hear these symphonies as manifestations of emotional unsettlement – either Haydn's, or in general. Haydn was an innovator, and it might be that he only wanted to create new sound-worlds in these and related symphonies, and that minor keys (generally underutilized in the Classical era) were fertile terrain for exploration. The "Farewell" Symphony needs little introduction. The story still stands that it was intended as a hint to Haydn's employer that it was time for everyone to go back to Vienna after an excessively long stay at Eszterháza. The final movement, in which the musicians stop playing and leave the stage, one by one, is justly famous. No less interesting, though, is the agitated first movement – a paragon of the "Sturm und Drang" style. The less well-known Symphony #39 is nearly as interesting, with a similarly "stressed" first movement. It goes to show, once again, that if you're a Haydn symphony, sometimes the only thing that stands between you and popularity is not having a nickname!

Isang Yun (1917-95) had quite a life. Born in Korea, he studied extensively in Germany, and was residing in that country in the 1960s when his homeland's secret police abducted him and took him back to South Korea, tortured him, and sentenced him to life imprisonment, supposedly for espionage. Thanks to the efforts of Western musicians, he was freed and released two years later, although he was prohibited from entering South Korea ever again. He wrote five symphonies (all in the 1980s), and two chamber symphonies (ditto). The first of the latter, recorded here, is scored for two oboes, two horns, and strings – a Haydn-ish orchestra, although the four wind instruments play a very prominent role. The work is in a single movement. Still, the music changes its pulse and character several times to give the rough impression of a three-movement work. The Chamber Symphony is an interesting and seamless conflation of Western and Eastern languages. A hint of the exotic, for example, is given by the almost obsessive insistence on rising two-note figures. Its mood is strange and unsettled, but not really disturbed. It is as if the music has its own intelligence, and is probing the world surrounding it, reacting to it, and forging ahead.

Given the juxtaposition of Haydn and Yun, it should come as no surprise that the Munich Chamber Orchestra plays on modern instruments. Their performance of the two Haydn symphonies is stylish and totally satisfactory, with no surprises one way or the other. (That would be a different Haydn symphony!) It is for the Isang Yun that I feel more inclined to praise Liebreich and the Munich Chamber Orchestra. This is a difficult work for the musicians – the wind instruments really have their work cut out for them – and I imagine that it can ramble if the conductor is not on his toes, sculpting the material and controlling the sonorities. Liebreich has convinced me, and I see more Isang Yun in my future! A church in Munich was the recording venue, and the engineers have kept the hazards inherent in such a location under control as well. In other words, great sound.

Copyright © 2008 by Raymond Tuttle