The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Korngold Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

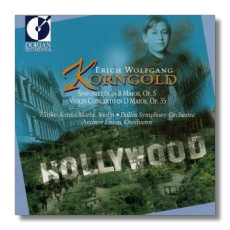

Erich Wolfgang Korngold

- Sinfonietta in B Major, Op. 5

- Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35

Ulrike-Anima Mathé, violin

Dallas Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Litton

Dorian DOR-90216

Executive Summary: Arresting in the Sinfonietta. Arrested in the concerto.

Of all the Austro-German composers contemporary with Richard Strauss in the early part of the century, one could have made a very strong case for the prodigy Erich Wolfgang Korngold as Strauss's Next Great Successor. Korngold had composed major works by the age of fifteen – indeed, before he was out of short pants. People marvel over the prodigy Mozart, but Mozart had an easier time of writing than composers from the mid-Romantic era on, when the musical language became more complex and the orchestral forces grew larger. This, of course, says nothing about musical quality. It's simply more difficult to handle a Strauss or Sibelius orchestra than a Mozart one, and Korngold was composing directly onto full score by age 13. Contemporary music has even more resources to master. Oliver Knussen is the last prodigy I've heard of, producing a symphony at age 13. Korngold's reputation peaked in the 1920s with his operas, especially Die tote Stadt. The Nazis cut short his concert career, when he was forced to flee to the United States and began scoring films. Despite a catalogue of beautiful music, it turns out that there's nothing in Korngold's output with the audacity of Strauss's Heldenleben or Elektra or with the profundity of Don Quixote, the Four Last Songs, Metamorphosen, or Rosenkavalier.

Someone once defined genius as the ability to come up with not merely the surprising thing – what we ourselves could have concocted if we were only many times better than we really are – but with what nobody could have foreseen and, once revealed, could not have figured out how the genius could have arrived at it. I once read all the poems of Yeats straight through. Every so often, I would say to myself, "Oh, I see how he's doing this. It's simply a matter of these groups of words and this kind of rhetoric." Then I'd come across a stunning poem for which there was absolutely no precedent in Yeats's previous work or anybody else's, for that matter. How did he hit upon it? It's the same with Strauss. Tod und Verklärung mostly rattles on like second-hand Liszt – better orchestrated, to be sure – until you get to the "transfiguration" theme, gorgeously lyrical in a brand-new way and unique to Strauss. There's nothing in Strauss's previous output that accounts for the creation of that theme (or the opening measures of Don Quixote, for that matter). While I've succumbed to the considerable charm of Korngold's music, it's never made the hairs on the back of my neck stand at attention. It turns out there was no Next Richard Strauss.

The Sinfonietta shows both amazing craft and real poetry. Korngold wrote it at the astonishing age of 15. In the first movement, a quick motive of sequential rising fourths generates a host of long-breathed themes. The young Korngold not only never loses his way, but mixes ideas among first and second subject groups, tightening the music more than the late nineteenth-century chromatic idiom usually allows. And the orchestra sounds both rich and clear. So many simultaneous lines sing distinctly, all due to Korngold's skill. If I quibble, I would have liked at some time sparer textures, but that's really a part of late-Romantic thinking: conceiving of music as melody, bass, and counter-melody or -melodies, with or without harmonic fill-in. I find analogies in the highly-detailed work of the Pre-Raphaelites and Art Nouveau. It's almost as if Korngold isn't happy if an instrument has nothing to do, much like Rachmaninoff in his piano music wants every finger moving and touching. By the second-movement scherzo, more of the orchestral same, I'd kill to hear a woodwind all by itself.

I just about get my wish in the highly imaginative opening to the slow movement (marked "dreamily"). Particularly effective are little shivers of sound (through discreet use of tuned percussion and harp) that became a Korngold fingerprint. Harmonically, the work often inhabits a place somewhere between post-Wagnerian chromaticism and Debussy. The little motive of consecutive fourths, singing this time, appears here as well. It's an unusual slow movement, in that among languorous and elegant song, quicker sections break out occasionally, like a terrier suddenly running hard at nothing in particular and stopping just as suddenly. It's a gambit difficult to bring off convincingly in music – that is, without the movement breaking down altogether – but the young Korngold does it apparently without breaking a sweat. The movement's ending is perhaps my favorite passage in the entire work. The finale begins fascinatingly and fugally, but it turns out to be a joke, as the fugue gives way after the first episode to something like a buffa overture, with the fugal subject rhythmically transformed and dressed in orchestral motley. The consecutive-fourth motive peeks out here and there until the finale brings down the house, with the consecutive-fourth motive peeking out here and there and finally going out in a blaze of orchestral glory.

Even it was written by a kid, this is one tough score, and Dallas and Litton do an admirable job keeping the music moving and clear. I could have stood sharper articulation in the strings at points during the finale, but all in all, a fine, committed account.

I heard first the Heifetz recording of the Korngold violin concerto, at the time the only available record. I asked a violinist friend of mine about it, 'way back in the 60s. His comment: "Pure corn and pure gold." Although completed in 1945 (apparently begun in the middle 30s), it's probably the last great German Romantic concerto (Berg's concerto is something other). Certainly it beats hollow Strauss's essay in the genre. By now, it's almost a repertory staple, and, if you ask me, it deserves its success. Almost every moment burns with inspiration. The best performance I've heard was live at a Louisiana Philharmonic concert, of all places, from a young German violinist Antje Weithaas, of astonishing, razor-sharp intonation (and Korngold gives the violinist hair-raising key changes without any orchestral support) and sweet tone. Like the Barber, the Korngold concerto really is "about" how well a violinist makes the instrument sing. Even Korngold's usual orchestral wizardry provides a frame which emphasizes this. Mathé's violin sounds dull, wrapped in flannel. She does best in the finale, but she should have grabbed us in the opening bars of the first movement. It's sort of like listening with a head cold. Even Litton and the orchestra seem infected – loggy and drab in the first two movements. In short, this won't replace Heifetz, Perlman, Shaham, or Hoelscher (a lovely performance led by Rudolf Kempe).

Sound is adequate, if not spectacular.

Copyright © 1997, Steve Schwartz