The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Chopin Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

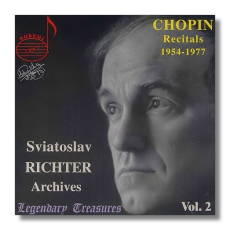

Frédéric Chopin

Sviatoslav Richter Archives, Volume 2

Recitals 1954-1977

- Scherzo #1 in B minor, Op. 20

- Scherzo #2 in B Flat minor, Op. 31

- Scherzo #3 in C Sharp minor, Op. 39

- Scherzo #4 in E Major, Op. 54 (rec. 15/4/65)

- Polonaise-Fantasie in A Flat Major, Op. 61 (rec. 10/11/54)

- Barcarolle in F Sharp Major, Op. 60

- Waltz in A Flat Major, Op. 34 #1

- Waltz in A minor, Op. 34 #2

- Waltz in F Major, Op. 34 #3 (rec. 26/8/77)

- Mazurka in C Sharp minor, Op. 63 #3

- Mazurka in C Major, Op. 67 #3

- Mazurka in F Major, Op. 68 #3

- Mazurka in A minor, Op. Posth #2 (rec. 25/8/76)

Sviatoslav Richter, piano

Doremi DHR-7724

In Bruno Monsaingeon's film Richter: The Enigma, Richter revealed to the camera his dislike of America and his feeling of panic when there. He rarely felt he played well, and this anxiety can be heard in his early Carnegie Hall recital from his breakthrough tour of America in 1960 ('Richter Rediscovered').

By 1965 and the Chopin Scherzi performances here, Richter seems much more comfortable, and recordings from the series of recitals he gave in April and May show him to be at the absolute peak of his form, combining the wild elemental power of his youth with some of the more poetic and deeply reflective qualities that had begun to emerge (try to hear the extraordinary Liszt Sonata from 18th May, once available on Philips and now on Palexa).

Here, in the 4 Chopin Scherzi, we finally have all the visceral excitement and passion missing in the 1977 studio recordings (on Regis), masterly and refined though those are. Twelve years earlier, timings are quicker for all the Scherzi, though that isn't to say that Richter plays faster throughout. What he does is to highlight more obviously the many-sidedness of these pieces, by playing the Presto sections much faster, and allowing the slow meditative sections all the time in the world. Nowhere is this more evident than in the 1st Scherzo in B minor, who's furious opening assault (truly Presto con fuoco) transforms into a brooding, heartfelt cry, in Richter's hands full of expression and freedom, before igniting again. Later, in the molto piu lento, Richter manages, as only he can, to almost suspend time, creating a feeling of motionlessness.

Listen how, in the C Sharp minor Scherzo, he layers the sound, the descending rippled accompaniments cascading like a water fountain, and a reminder of the great colourist he was.

Harold C. Schonberg commented in his review of the concert that these were "interior" performances. Yes. But that's only part of the story. What is extraordinary to this reviewer is the way in which the playing at times takes on an intimate reverence, full of poetry and the darkest solitude, at other times (the closing bars of the B minor and C Sharp minor Scherzi for example) a declamatory and even openly virtuosic approach, one which is a reminder that Richter could still play the showman of his youth.

Occasionally one misses the extra breadth of the studio recordings, as in the opening of the B Flat minor Scherzo, which sounds angry and forceful in 1965 and grandly Olympian in 1977, though generally the later accounts feel somewhat too removed and controlled by comparison.

The other performances are all fine, with the Barcarolle and Waltzes available (in better sound) on Orfeo, and some of the Mazurkas a first releases, but it is the Chopin Scherzi which you will not want to be without, despite the muffled and slightly distorted sound.

Copyright © 2006, Alex Demetriou