The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

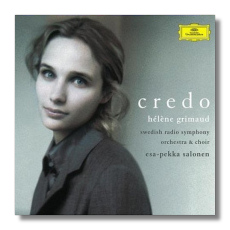

Credo

- Arvo Pärt: Credo

- Ludwig van Beethoven:

- Choral Fantasy

- Piano Sonata #17 in D minor "Tempest", Op. 31 #2

- John Corigliano: Fantasia on an ostinato

Hélène Grimaud, piano

Swedish Radio Symphony and Choir/Esa-Pekka Salonen

Deutsche Grammophon 471769-2 DDD 68:31

Also released on Hybrid SACD 471869-2:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

For her first Deutsche Grammophon release, French pianist Hélène Grimaud has assembled a quirky, provocative program. According to Grimaud, the disc's "center of gravity" is Beethoven's Choral Fantasy, a work sometimes deprecated as a mere foreshadowing of the Ninth Symphony's "Ode to Joy." Grimaud and Salonen minimize its portentousness with a reading that is as lean as a marathon runner. Classical ponderousness has been traded for objectivity; instead of making us nod our heads and sagely comment, "That's great music," the performers strip the work down and somehow make it more enigmatic. Grimaud does much the same with the "Tempest" Sonata, except she takes it a little too far, I think. I know of no other reading that is so willfully "unstormy." Still, playing like this is well within the French tradition, even if Grimaud has put her idiosyncratic twist on it.

The Beethoven pair is book-ended by relatively recent works by John Corigliano and Arvo Pärt. The former's Fantasia on an ostinato was written as test piece in 1985 for the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition. The ostinato is taken from the second movement of Beethoven's Seventh Symphony – that literally monotonous yet fascinating series of repeated notes. Corigliano rings disturbing changes on this ostinato, and the work challenges not just the pianist's technique but her ability to reconcile the old and the new. Grimaud succeeds, perhaps in part because she appears to have more than a casual interest in Novalis's Universalist theories, which posit that "all is one."

The title work, written by Arvo Pärt in 1968, complements Beethoven's Choral Fantasy, because there are few works, of course, scored for piano, orchestra, and mixed chorus. It also complements the Corigliano. That's because the Credo is based on an older work, not by Beethoven, but by Bach - the very first prelude from Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier. Pärt's 15-minute work is a shattering expression of faith, and of the dangers that can result from adhering to it uncritically. While passing Bach's musical idea among the musicians, they misinterpret it, if you will, and the center of the Credo is a shatteringly violent depiction of chaos. It is only after this firestorm that rational peace is restored. This is the highlight of the CD, and in fact Credo is this CD's omnibus title.

Conceptually, then, this disc rates an A, while the performances are a solid B+, rising to an A in the Corigliano and Pärt. The engineering complements the objectivity of the performances. The chatty booklet notes include Grimaud's reflections on the music, and an interview with Michael Church in which we also find out about the pianist's affection for wolves, and her Scriabin-like fascination with synaesthesia – the association of music with colors.

Copyright © 2004, Raymond Tuttle