The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Atterberg Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

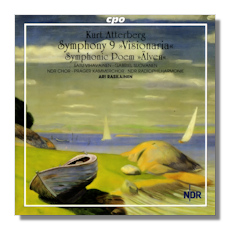

Kurt Atterberg

- Symphony #9 "Sinfonia Visionaria", Op. 54

- Symphonic Poem "The River" (Älven - från fjällen till havet), Op. 33

Satu Vihavainen, mezzo-soprano

Gabriel Suavanen, baritone

North German Radio Choir

Prague Chamber Choir

North German Radio Symphony Orchestra/Ari Rasilainen

CPO 999913-2 60:35

Summary for the Busy Executive: Of gods and the river.

Kurt Atterberg, one of the most profoundly gifted composers of his generation, made the symphony central to his output, finally winding up with nine, just like Beethoven and Mahler, and all the while working at least two other full-time jobs: electrical engineer and administrator of the Swedish composers' society. He also had a side gig as an internationally-known conductor. For years I knew only his Suite #3 for strings – a lovely work, which for some reason failed to get me to look for more.

Definitely my loss, for now CPO has launched an Atterberg mini-series, which includes all the symphonies and which has revealed a much larger figure to me. Atterberg's major symphonic contemporaries – Mahler, Elgar, Nielsen, Sibelius – needn't scrunch to make room just yet, but to say Atterberg's achievement fails to reach their level doesn't condemn it. It still has poetry and power of its own.

The tone poem Älven – The River has its roots in Smetana's Moldau. However, one notes significantly different points of view. Smetana essentially builds from a single tune. Atterberg builds in little pieces, many of which have nothing to do with one another. Also, Atterberg doesn't describe the course of a particular river. The river provides a metaphor, an excuse to sing about the Swedish landscape. The tone poem assumes, to some extent, the manner of a travelogue – "Sweden: Enchanted Nature." It runs fairly loose, but it does impress you with the sheer amount of invention in it. The episode as the river passes through a harbor town is especially striking, as foghorns, buoys, sailor songs, and the sounds of the dock jostle one another – the kind of texture Ives pioneered. However, everything else paints nature: rushing water, crashing waterfalls, still lakes, and, finally, the open sea. One theme sort of runs through in various guises, but not in any obviously apparent way and not all that strictly. Nevertheless, Atterberg has mastered the shaping of symphonic time to such an extent that you experience the work pretty much as a whole.

Atterberg's Ninth Symphony, with soloists and chorus, is an altogether different affair, both in the composer's attentiveness to architecture and in his ambition. Ninth symphonies usually have composers looking back over their shoulder at Beethoven. Even Shostakovich's sardonic Ninth, looks back to that monument, if only to thumb its nose and grin. One has trouble pinning down Atterberg's Ninth. Is it cantata or symphony? I think it lies closer to cantata. Atterberg set sections of the Icelandic Poetic Edda, emphasizing those parts relating to Ragnarök, the Scandinavian pagan story of the end of the world. You get bits of it in Wagner's Ring des Niebelüngen. In fact, "Götterdämmerung" (twilight of the gods) translates into German the Old Norse "Ragnarök" (fate of the gods). Their fate is not a joyful one. Odin, Thor, and the gang – they all get killed.

Aside from its position as a glory of world literature, why did Atterberg choose to set it? The liner notes suggest that the two nuclear detonations at the end of World War II spurred Atterberg in this direction.

Atterberg doesn't give us anything like a classical symphony, and yet the music proceeds symphonically. Symphonic narrative seems almost part of his DNA. Even so, one can see a lot of brainwork here, most notably in the setting of the poetic refrains throughout the work. Each refrain gets its own music, which recurs at each appearance of that particular refrain. The music in between differs but leads inexorably to the refrain. It's more difficult to accomplish these transitions than it may sound at first. As fits a folk text, Atterberg uses a folk-like idiom (sort of like Lars-Erik Larsson's Disguised God infused with the Vitamin B12 of symphonic sweep) and in doing so meets and overcomes many challenges. The verse is generally in octaves – two quatrains – with the major break coming with the second quatrain. The music tends to move like most ballads: first two lines a unit, third line contrast, fourth line either a transition or a wrap-up, depending on which quatrain. This is a long text, and a lot of that can get tiresomely predictable, but Atterberg has the smarts to know when to vary and the talent to let you forget his considerable art. The battle music especially, with its fanfares from all corners of the sky, gets your blood racing. If it's not the greatest symphony of the century, who cares? It's incredibly effective. I'd even call it a masterpiece.

Rasilainen and his North German Radio musicians give committed, exciting performances of both works. Baritone Gabriel Suavanen sings with a dark, haunted quality, and Satu Vihavainen as the omniscient oracle tells of great sorrow. Contrary to popular belief, knowing the future makes nothing easier, in the long run.

Copyright © 2009, Steve Schwartz