The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Weiss Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

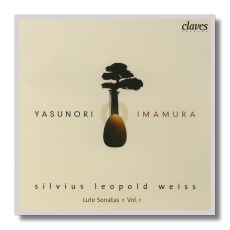

Silvius Leopold Weiss

Lute Sonatas, Volume 1

- Sonata in B Flat Major

- Prélude and Fantasie in C minor

- Sonata in A minor

Yasunori Imamura, lute

Claves 50-2613

In 1728 after hearing Silvius Leopold Weiss (1687 (or '86) to 1750) play in Berlin, Wilhelmine von Bayreuth, sister of Friedrich II, wrote that so virtuosically did he excel on the lute that all who follow "n'auront que la gloire de l'imiter" (may do no more than imitate him). That's a challenge for any modern performer too. Yasunori Imamura in the three pieces which make up Lute Sonatas Volume 1 meets it exceedingly well – especially since only the tablature manuscripts (the fingering, rather than the pitch of the notes) survive.

An exact contemporary of J.S. Bach, Weiss (whose father – also his first teacher – was a lute and theorbo player) was born in Breslau (Silesia) in what was then Bohemia and is now in south west Poland. At an early age he was invited to play before emperor Leopold I; he then held several player positions in various German towns before entering the service of the Polish prince Alexander Sobiesky, who was exiled in Rome. It was in Italy that Weiss met many of the leading Italian innovators including Scarlatti father and son, and Handel. Their influence is evident in the music on this CD as a certain gentility and melodic intricacy; as well as some of the naming conventions: Weiss uses "Introduzione" and "Presto" as well as the more usual French dance movement names in these sonatas. On Sobiesky's death, Weiss moved to Dresden where he spent the rest of his life, and where he was able to command an unusually good salary.

His compositional catalog is substantial: 650 solo lute works – for the 11-course (a "course" is a string pair) lute until about the time we know he was in Dresden; thereafter for the 13-course instrument. The latter took over from the former as the eighteenth century progressed, so the change Weiss made was probably as much a matter of musical development as of geography. On this recording Imamura plays a modern (Stephen Gottlieb, London 1993) 13-course "baroque" lute, which has a warm, round sound. It is possible that if Weiss had composed for other than – or additionally to – the lute, later opinion would place his work alongside that of Bach and Handel. You won't hear quite their melodic inventiveness of either in these works. But you will hear original, memorable and entirely pleasing themes developed at length for the listener, as well as the player. And you will be in the presence of a supreme creator totally at ease with the sound of the lute and full of thoughtfully-crafted material invariably developed with an almost romantic feel to them, although it's hard to believe that some of Imamura's improvisational gift doesn't at times get the better of a certain discipline on which the music thrives.

This disk contains music from Weiss at the height of his powers: the B Flat Major and A Minor Sonatas in seven movements, each just over half an hour and the "Prélude and Fantasie" in C minor lasting a little more than five minutes. The style of the music and playing could hardly be more different from the softer delicacy of lute music from the Elizabethan era several generations earlier. This is robust, almost forceful music which in some ways looks forward even to Mozart in its very penetrating and colorful tonal breadth and muscularity. It's music with a new and inventive way of blending introspection and invention. It never dallies. It's full of variety too. Particularly striking to listeners not familiar with Weiss will be the many changes in tempo and extent to which rallentandi and accelerandi, for example, support – dictate even – both the mood and the structure of the music within the same movements. The opening of the C minor Prelude, for example, is taken more slowly than equivalent pieces of the high Baroque with which you are likely to be familiar. The range of tempo during the ensuing Fantasie surges every bit as stridently as the sturdiest of Bach's solo instrumental suites.

If there were one minor criticism of Imamura's playing, it would be that his dynamic range could be greater. Of the recording that the reverberation be slightly less. There may be just the hint of showiness in his performance: comparisons with the Robert Barto set on Naxos are instructive here. Imamura's playing, though, helps the music: it genuinely communicates its intent and sentiment, never strays towards what a high baroque German lute composer might be thought to have written without knowing such repertoire. Indeed, the particularities of this music – and there are now to be two complete cycles of it – make it worthy of attention from lute aficionados and lovers of the period's instrumental music when it's played as delicately and sensitively as this.

What an attractive and informative booklet comes with this CD… clearly laid-out and nicely divided into sections on Weiss' life and works, Imamura and the three pieces featured on what will surely be a set to watch out for as future volumes are released. A note in the booklet also points out that the spelling "Silvius" is grammatically and historically incorrect: although Weiss always signed himself "Silvius", the only engraving of him, which dates from 1766, introduced the error. It has wrong birth and death dates too – as does the digital information on the CD when revealed in iTunes, say. So the misspelling (and the dates for that matter!) have stuck in some quarters. The words under that same engraving of the composer, "Only Sylvius [sic] should play the lute" may compensate. You are urged with this CD to see if that (and yet another "overlooked major composer status" for Weiss) may not perhaps be true!

Copyright © 2007, Mark Sealey