The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rubbra Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

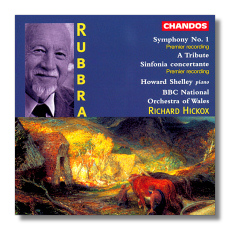

Edmund Rubbra

- Symphony #1

- A Tribute

- Sinfonia concertante *

* Howard Shelley, piano

BBC National Orchestra of Wales/Richard Hickox

Chandos CHAN9538 71:13

Summary for the Busy Executive: One of the great Chandos releases. Buy this.

Edmund Rubbra's symphonic cycle has long been admired as one of the finest of the century. So tell me why his first symphony, completed in 1937, received its first recording in 1995. This CD contains another important première, the Sinfonia concertante of 1936, Rubbra's first published large-scale orchestral work. The smaller Tribute, written in 1942 for Vaughan Williams' birthday, has appeared on several recordings.

I have no idea why the general classical-music public hasn't embraced Rubbra's music. The language raises no terrors to anyone who can get through Vaughan Williams or Walton. The music communicates vigorously and directly. However, I suspect that Rubbra's biggest hit is his orchestration of the Brahms Handel variations. I strongly commend Chandos for undertaking the complete symphonies and for all the other Rubbra it has given us along the way.

Rubbra studied with Holst, a marvelous composer known mainly for The Planets, which turns out not terribly characteristic of his output. From Holst, he became interested in Tudor composers. Holst's visionary intensity probably also found an echo in Rubbra. Musically, Rubbra to some extent begins in late Holst, the Holst of the unfinished symphony, but without imitation. Like van Gogh, Holst resists fruitful direct imitation. Very few composers want to end up sounding like second-hand anybody, and Holst's artistic profile is simply too strong. Fortunately, Rubbra had a strong character of his own.

I'd say the symphony has been well worth the wait, if I understood why I had to wait at all. It's a terrific work, and shows a huge architectural reach as well as great power. From the very first, it appears that Rubbra pursues an individual symphonic path, with almost no reliance on classical forms like sonata-allegro. The sonata depends largely on contrast – classically, on key-contrast. However, when tonality becomes fluid, as it did among most twentieth-century composers, including tonal ones, composers had to find some other point of contrast or another rhetorical principle. In the first symphony, Rubbra replaces the principle of contrast with one of "becoming." Wilfred Mellers (a Rubbra pupil) and others trace this kind of architecture back to the Tudor instrumental fantasia. The liner notes (by Robert Saxton and Rubbra expert Adrian Yardley) claim that the entire symphony essentially grows out of the opening measures. I'll take their word for it. However, it's immediately clear that Rubbra throws out more inventive strokes in his first paragraph than many composers achieve in an entire movement. The overall architecture – 3 movements, fast-fast-slow, with the last movement longer than the first two combined – points to a master largely free to pursue his own train of thought.

The symphony grabs the listener from the first with a series of bold, vigorous, and splashy fanfare ideas. At the same time, there are rhythmic features that also foretell much of what happens in the movement, and a chromatic "subplot" developed on separate lines also throughout the movement. Essentially, the composer invites us to follow at least three different simultaneous paths as they meander, merge, fork, and cross. Rhetorically, the movement starts from high energy and then drains. A "bucolic" scherzo follows. Saxton and Yardley hear similarities to the scherzo of Vaughan Williams' Sixth, but it seems to me on an altogether grander scale than a Vaughan Williams scherzo. It's more heavily-scored, for one. Incidentally, the usual charge against Rubbra early on was that he was a drab scorer. Certainly, there's little instrumentation that calls attention to itself as such. But this is really a view of scoring as "coloring in" the lines of music already composed. It seems to me, however, that for really great orchestrators, the conception of color is inextricably linked with the music. Ask yourself, for example, how Strauss could have scored Till Eulenspiegel any differently. Rubbra's orchestration has color, but color appropriate to the music itself. The final lento illustrates the "becoming" principle most clearly. Here, the rhetoric moves from an energy low and gains intensity as it progresses to material that definitely sounds like the first movement. In this sense, it's the first movement reversed or the head of the first movement swallowing the tail of the last. The symphony doesn't end as much as it begins again.

Rubbra's Tribute to Vaughan Williams was part of a BBC multiple commission on the occasion of the older composer's 70th birthday – the other composers including Lambert, Alan Bush, Jacob, Maconchy, and Robin Milford. Lambert contributed his Aubade and Patrick Hadley his One Morning in Spring, both lovely works. Lambert admired Vaughan Williams without following his lead as a composer. The Aubade owes far more to Stravinsky than to VW. Hadley very obviously comes from Vaughan Williams' "folk" side. Rubbra without direct imitation nevertheless owes much to the "cosmopolitan seriousness" of Vaughan Williams and Holst. These two composers (as well as Walton) showed musicians of Rubbra's generation how to create a modern English music, just as Britten and Davies have influenced subsequent generations. Rubbra's Tribute is a gravely beautiful andante, with soaring string passage work slightly reminiscent of Vaughan Williams' Fifth and a scherzo-ish middle section which seems a cousin of the scherzo of Vaughan Williams' Fourth. However, it doesn't have you saying "How very like Vaughan Williams" but "How beautiful."

Rubbra avoided calling the Sinfonia concertante a piano concerto, despite its considerable part for solo piano, and, hearing the work, one immediately understands why. This is more a symphony in which the piano takes a leading role, rather than an opportunity for individual heroics or display. A work of high energy, it lays out in three quite unusual movements. The first – "Fantasia: Lento con molto rubato – Allegro" – is what I call a "corkscrew," beginning intently and constantly ratcheting up. The second, a scherzo "Saltarello," blows off a lot of steam, until the brilliantly-conceived trio, which consists practically entirely of long notes on a single tone. It's as if the dancers are completely winded before they find the energy to jump up again. The finale, a monumental slow Prélude and fugue conceived in part as a memorial to Holst (who died in the year Rubbra began it). In his maturity, Holst became fascinated by canon (writing several in as many different keys as there were parts) and fugue. Too much, however, can be made of the Holst connection, for musically it seems to me that Holst and Rubbra are almost diametric opposites. I contend one can hear the difference in this movement and, say, Holst's Terzetto. In Holst, one hears tremendous focus and concision. In Rubbra, one hears music that always wants to expand and flower – explosion as opposed to implosion – although one can never accuse Rubbra of over-inflation. It says much for Rubbra that the listener is less aware of the fugue than of the elegy. The work closes beautifully, with all the emotion earned.

I can't praise this CD highly enough. Hickox and the band never let Rubbra's long symphonic arcs droop and manage it without melodramatics. Howard Shelley is a hero for taking on in some ways an ungrateful part and making majestic music from it anyway. He dazzles in the saltarello movement and speaks eloquently in the Prélude and fugue. The poetry of the close depends almost entirely on him, and he steps up to the plate. The recorded sound is Chandos' usual superb while maintaining the illusion of natural balance.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz