The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Hindemith Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

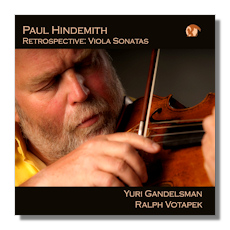

Paul Hindemith

Retrospective

- Sonata for Viola & Piano in F Major, Op. 11, #4

- Sonata for Viola, Op. 25, #1

- Sonata for Viola & Piano in C Major (1939)

- Capriccio for Cello & Piano, Op. 8 #1

Yuri Gandelsman, viola

Ralph Votapek, piano

Blue Griffin BGR277 58m

Paul Hindemith (1895-1963) was one of the great 20th-century composers, arguably the greatest German-born composer of his era after Richard Strauss. But he hasn't fared so well lately, or so it seems. Shortly after I received this recording I came to wonder about Hindemith's seeming recent neglect. I recalled that a half century or so ago he was a far more popular composer, often spoken of in the same sentence with Stravinsky, Prokofiev, Shostakovich and other luminaries of the 20th century. I paged through a 1968 Schwann catalog (my oldest surviving one) to confirm my suspicions: Hindemith had more recordings listed in it than Shostakovich! Today Shostakovich has about three times as many recordings as the fading Hindemith. Further, even Poulenc, Vaughan Williams and Villa-Lobos appear to attract more attention than Hindemith, at least in the recording studio. So what has happened?

Well, it's difficult to explain Hindemith's decline, especially since he has several large works in or near the standard repertory – Symphonic Metamorphosis of Themes by Carl Maria von Weber, Mathis der Maler Symphony, Konzertmusik for Brass and Strings, and Nobilisima Visione – and so you would expect him to retain a reasonably high level of currency. I think one might surmise that Hindemith's large output in the chamber music genre has both served his reputation well but sabotaged his popularity, because he often tended to write music for odd combinations of instruments or for less popular instruments like the viola, which is relatively neglected alongside its siblings, the violin and cello. Yet, Hindemith's chamber works were usually well crafted and generally quite accessible, as this new recording on the Blue Griffin label clearly demonstrates.

All the works here are attractive and splendidly performed, ingredients that should make this CD appeal to most chamber music mavens. The Sonata for Viola and Piano, Op. 11, #4, dates to 1919 and is thus a very early work in Hindemith's output. It is arguably his most popular chamber composition. Hindemith himself played the viola (along with a slew of other instruments) and so it is little surprise that he could write so well for this instrument. The work opens with a lovely, utterly memorable melody and the mood remains light throughout this three-minute movement. The second movement, which is only slightly longer, is just as lyrical and appealing in its theme and variations. The composer noted the "folksong" character of the melodic material here. The finale, at over nine minutes, is also a theme-and-variations scheme, but with a bit more muscle. That said, the music is still mostly light and songful.

The five-movement solo Viola Sonata, Op. 25, #1, has a tougher veneer and, save for the third and fifth movements, more energy and bite. The fourth movement comes on like a Prokofiev Toccata: the composer likens its mood to something wild and calls the tempo "raging". Overall, the work yields an expressive depth that might take a second or third listening to fully appreciate.

The 1939 Sonata for Viola and Piano in C Major is a work from Hindemith's maturity, and came at a time of crisis in the composer's life, when he had fled Germany because of the Nazi insanity, first settling in Switzerland (1938) and then the United States (1940). To me, this Viola Sonata is the most substantive work on the disc. The first movement is heroic and conflicted, often featuring dark piano writing: here, in fact, the piano is as interesting, maybe more interesting than the viola. The ensuing panel is lively but again divulges a sense of conflict, with both the viola and piano often seeming to goad each other toward discord. The third movement features the viola seemingly frustrated or searching one moment then singing dreamily the next. The finale is bright in the outer sections and features a playful central episode whose deft humor seems at odds with much that has preceded.

The closing work on the disc is the earliest, the Capriccio for Cello and Piano, Op. 8, #1, heard here in a fine arrangement by the violist Yuri Gandelsman. It is a tuneful light work of irresistible charm. As for the performances on this CD, they are, as suggested above, uniformly excellent. In all works the players infuse the music with spirit, capturing lyrical elements with sensitivity, lively music with vitality and drive, and profound music with an intensity and probing sense. Gandelsman and Votapek make fine partners, seeming perfectly at home with the composer's rather unique expressive manner. Gandelsman has a splendid tone and all-encompassing technique, and Votapek here shows why he has been among the leading American pianists of his generation.

Neither artist on the disc will likely be familiar to younger readers. Tashkent-born Yuri Gandelsman won the National Viola Competition in the Soviet Union in 1980 and held positions in the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra, Moscow Virtuosi and Israel Philharmonic. He has collaborated with such luminaries and Sviatoslav Richter, Yuri Bashmet, Yevgeny Kissin and Oleg Kagan. Ralph Votapek was the winner of the first Van Cliburn Competition in 1962. He went on to appearances at Carnegie Hall and with the major orchestras of New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, London and other cities across the globe. I well remember seeing his consistently fine performances on PBS television in 1960s.

The sound on this CD is excellent and I can only say that if you enjoy chamber music from the 20th century, this disc should certainly have much to offer you.

Copyright © 2013, Robert Cummings