The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Krenek Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

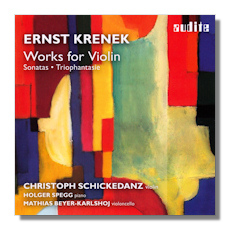

Ernst Krenek

Works for Violin

- Sonata for Violin Solo #1, Op. 33

- Sonata for Violin Solo #2, Op. 115

- Sonata for Violin & Piano #2, Op. 99

- Trio-Fantasie for Piano & Strings, Op. 63

Christoph Schickedanz, violin

Holger Spegg, piano

Mathias Beyer-Karlshoj, cello

Audite 95.666

For many, Ernst Krenek, who spanned almost all of the last century, living from 1900 to 1991, is more of a neglected name than a composer to whom they turn for profound, stimulating and beautiful music. There are only a few dozen CDs in the current catalog devoted to his music. This hardly reflects his potential stature; and certainly not his prodigious output. Krenek's musical training began at the age of six and he died aged 90 having recently experimented with electronic music. One of Krenek's most remarkable characteristics was an ability not merely to move with the musical trends and developments of "his" century, but also to map them onto his own unique style. He moved from his home city, Vienna, to Berlin and Paris, observing and absorbing (but always making his own) the music that was being written and performed there… he studied with Schreker and at the Berlin Conservatory. Aspects of Stravinsky's neo-Classicism, of the Second Viennese School's composers (Berg and Webern in particular) and of jazz made distilled adjuncts (inspirations, perhaps) to his own original and supremely self-confident style.

Here is exciting and technically brilliant playing on a new CD that both helps to illustrate Krenek's place in the pantheon. It draws the listener in; it invites them to look more deeply. In the foreground of the four explosive yet finely-crafted works on the CD are overt, fresh and pressing modernism; the tension; the feeling that only musical essences can resolve such anxiety; and a lack of sonic distractions.

For all the player(s)' brilliant blend of intensity with expression, the music on this CD – recordings of none of which are otherwise available – is communicative and immediate. Christoph Schickedanz in particular plays as though neither leaning towards an audience, nor implicitly advocating any ideal or musical/historical presence. The music is there, his approach seems to be suggesting, as music to be listened to. At the same time, the aforementioned tautness (without which the idiom here would be meaningless) is immediate. It's presented in such a way that one is left with a satisfying sense of completion and peace almost. Nothing is either underlined or underplayed; the music unfolds at its own pace.

At times one senses one is straying into Debussy (in the middle of the Trio-Fantasie, Op. 63, [tr.8], for instance). At other times almost into the staccato insistences of Bartók (at the start of the second solo violin Sonata, Op. 115, [tr.9]). At others pure serialism. And yet others (towards the last third of the same Trio-Fantasie), an amalgam (Krenek never works in pastiche) of earlier Viennese traditions.

These players, then, are fully aware of the potential pitfalls both of offering Krenek's music as merely illustrative of twentieth century trends, and of concealing its innate beauty and strengths with references to other forms. Both are avoided. This is music that stands on its own merits. The string sounds of both Schickedanz's violin and the cello of Mathias Beyer-Karlshoj in the Trio are sweet but neither sickly nor cloying. Their phrasing is as definite and punchy as it is melodious; it's sculpted in such a way as to elicit an emotional response which we can articulate – rather than of which we are somehow only vaguely aware… design excludes amorphousness. Then Holger Spegg's piano playing in both the Trio and second Sonata for violin and piano, Op. 99, is supportive and unobtrusive in equal measure.

There was a brief period of the composer's life (from 1925 to 1927, in Kassel and Wiesbaden) when he worked in the operas there. Schickedanz and Beyer-Karlshoj are both aware of the inherent (though at times consciously suppressed) drama in Krenek's string writing. This is analogous, almost, to the energy in Bach's great solo string works. Such a potential parallel is strengthened by the scale of some of the movements here: the first (largo) and third (adagio) of the first Sonata, opus 33, are nine-and-a-half and twelve-and-a-half minutes in length respectively.

Schickedanz does not allow this sense of space (indeed, Krenek marks the third movement, "moglichst ruhevoll" – "as calmly as possible") to rest, lose focus or relax. Nor to run on the spot, attempting to make a point more than once. Instead he hints at the almost symphonic dimensions, certainly the aura of the previous century, which inform the sense which the music makes to and for us. Once again, the work – written without bar lines – is a tour de force, and a homage. It's vital that it be played without any sentimentality; this could emphasize the scale over the essence of the music. Schickedanz does exactly that. The playing does not lack reflection or thought. It just flows naturally and without apparent propulsion – other than the musicality of the performer(s).

The CD's acoustic is close and without obtrusive "atmosphere". The booklet contains biographies of the players, and sets the scene – emphasizing the way in which the variety of these works mirrors the varied development of Krenek's musical career. If you're new to Krenek, this CD is an excellent place to start. It exposes purposefully, yet casually, many of the composer's most important facets. At the same time, it simply contains well over an hour of splendid, enjoyable and energetic music played expertly and with real insight. Not once do the players – especially Schickedanz – fail to impart drive by giving in to the contrast or dichotomy between passion and spontaneity, or expression and technique. Theirs is a holistic conception and execution which can be thoroughly recommended.

Copyright © 2013, Mark Sealey