The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

SACD Review

SACD Review

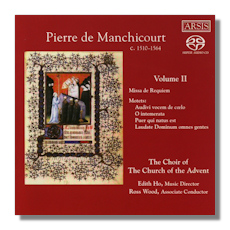

Pierre de Manchicourt

Volume II

- Missa de Requiem

- Audivi vocem de cœlo

- O intemerata

- Puer qui natus est

- Laudata Dominum omnes gentes

The Choir of the Church of the Advent, Boston/Ross Wood

Arsis SACD406 Hybrid Multichannel SACD

This is an outstanding recording, and one that should be snapped up without a moment's hesitation.

Pierre de Manchicourt (c.1510-1564) is not so well known – and nowhere nearly so suitably appreciated – as other Renaissance polyphonists. But merely on the evidence of this collection – and that of Volume I in the Arsis series, also by the Choir of the Church of the Advent, Boston, (SACD400) – that surely must change. Manchicourt's music has splendor, containment, a transparent devotion and great beauty. Here is a performance which is superbly recorded with much appropriate atmosphere yet which lets the music penetrate to your very soul. The choir is always in control of the music: its richness and depths have strengths all of their own.

Again, Edith Ho (Music Director) and Ross Wood (Associate Conductor) of the unpretentious yet increasingly acclaimed parish church choir from Massachusetts have conceived and produced a wonderful recording. The music is warm, immediate and inspiring. The performance perceptive, respectful yet full of energy and expression to match. It's hard at times to believe that one isn't listening to the gold of Palestrina; Manchicourt's idiom is redolent of the glories of Taverner and Tallis too.

Manchicourt was from the Low Countries, being born probably a generation after Taverner and five years after Tallis, in 1510. We know little else; except that he died 50 or so years later in Madrid, in 1564, where he worked as maestro di cappella for Philip II. From this we can conclude, perhaps, that Manchicourt was (or became) a Catholic: both Philip and his father, Charles V, were staunch defenders of the Counter Reformation. He composed a dozen or so motets, most of which were published in his lifetime, and nineteen masses, few of which were.

This recording offers the Missa de Requiem and four motets. The Requiem is closer in feeling to that of Fauré than of Verdi in that it conveys serenity and resignation, almost, rather than any kind of triumph in overcoming death. Manchicourt sets the plainchant in the upper voice and slides contrapuntal movement around it adding to the sense, frankly, of great control and detachment. The singing by the Choir of the Church of the Advent is very pleasing indeed, not least because they are so in tune with this stance: their phrasing is spot on, the conviction with which each portion is structured then projected compelling. There's a naturalness to the way each line is styled, each passage textured, that makes the listener regret when the piece is over.

The motets all display the integration and self-contained strengths first elaborated by Manchicourt's contemporary, Nicolas Gombert (c.1490 - c.1556), who was also employed at the Spanish court. Again, counterpoint is crucial, prime, overwhelming, almost. But in a good sense: the unbroken lines achieve their effect not through splash or gloss; but through consistency and a sublime sense of wholeness. In both these cases, the singers might have had to work hard not to get lost in the density and passion. The Choir of the Church of the Advent is more than up to this task: they seem to reach the end of each piece (and indeed of the Requiem) with all the confidence of having known just where it was leading through every note. Control is not everything, though it counts a great deal. Vision is just as important. And a measure of humility: this is exceptionally beautiful music which will convey its loveliness to us in its own way and of its own accord, almost! The Choir has taken on the role of conveyors more than interpreters; but only because the music has sufficient strength for that to happen.

Manchicourt was composing at a time when the praxes and idioms of choral polyphony were well established; his work forms part of that of the "fourth generation" of such composers from the Low Countries as Willaert, de Rore, Clemens non Papa and Crecquillon. There is something special about each of these. Something distinctive that seems only to come at a time when a tradition has reached the end of its useful life and its practitioners owe more to their own preservation as makers than that of the school, or idiom. By Manchicourt's time, new approaches to polyphony were catching on. But his music is shown on this recording to be as vibrant, profound, purposefully intricate and downright beautiful as anything written before.

The SACD acoustic is excellent, then, the music-making exceptional; there is a useful introductory essay by Ignace Bossuyt from Belgium which also presents the bibliography of Manchicourt's manuscripts. The fact that Manchicourt is under-represented on disc is not the reason to go for this recording immediately; nor hardly the sumptuous sound (though that's a huge bonus: the recording amply reflects the open acoustic of the Church of the Advent, Boston); still less any curiosity or rarity value for Manchicourt. It's the consistently excellent music in and of itself, robustly and sensitively performed by such accomplished ambassadors and advocates for the composer that make this a recording that stands a good way out from the crowd.

Copyright © 2009, Mark Sealey