The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rossini Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Blu-ray Review

Blu-ray Review

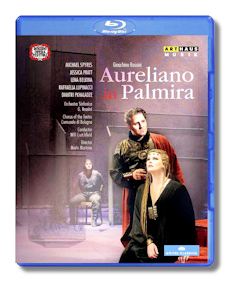

Gioachino Rossini

Aureliano in Palmira

- Aureliano - Michael Spyres

- Zenobia - Jessica Pratt

- Arsace - Lena Belkina

- Publio - Raffaela Lupinacci

- Oraspe - Dempsey Rivera

- Licinio - Sergio Vitale

- High Priest - Dimitri Pkhaladze

- Un pastore - Raffaele Costantini

Lucy Tucker Yates, fortepiano continuo

David Etheve, cello continuo

Chorus of the Teatro Communale di Bologna

Orchestra Sinfonica G. Rossini/Will Crutchfield

Critical Edition of Opera by Will Crutchfield

Recorded Live at the Teatro Rossini (Rossini Opera Festival), Pesaro, Italy, August 2014

Stage Director - Mario Martone

Set designer - Sergio Tramonti

Costume designer - Ursula Patzak

Arthaus Musik/Unitel Classica Blu-ray 109074 3:20:35+14:00 Bonus PCM Stereo DTS-Master Audio

Also available on DVD 109073: Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan - ArkivMusic - JPC

Rossini's popular operas like The Barber of Seville, L'italiana in Algeri and La Cenerentola have tended to obscure his somewhat less successful efforts such as Aureliano in Palmira (1813). But Aureliano, despite a lukewarm premiere, was initially quite successful throughout Europe and England. By the middle of the 19th century, however, it had faded and remained neglected until recent times. This recording, as is noted in the heading, uses conductor Will Crutchfield's critical edition of the work, which employs additional music not even used at the 1813 premiere. It's not possible to know for sure what was in the original version since no autograph score survives. Thus, the new music here was not used at the premiere perhaps because some or all of it was composed for subsequent performances or because changes in the score were made at the last minute when tenor Giovanni David as Aureliano took sick and was replaced by the lesser Luigi Mari who had trouble with the high tessitura. Whatever the case, this appears to be the most complete performance/recording of the work ever presented, as it contains what could be more than a half hour's additional music than the three other recordings of the work, two of them on Bongiovanni and one on Opera Rara. I say "could be more than a half hour's additional music" because tempo selections could be a factor too, as I will delve into later on.

Despite the neglect of this opera over the years, listeners will recognize much of its music: the Overture and first chorus, Sposa del grande Osiride, were recycled by Rossini in The Barber of Seville. Moreover, Stravinsky, who was proud to admit to thieving in many of his compositions, reused some of the music from the overtures in the finale (or third deal) of his ballet Jeu de cartes. Overall, listeners coming to Aureliano for the first time will find its music quite attractive and this production of the work reasonably good. The stage at the Teatro Rossini in Pesaro, Italy is small but the costuming, lighting and sets (modest though they are) are quite good in this traditional treatment of the story by stage director Mario Martone. This is no visual extravaganza or lavish production then, but it is a solid, at times imaginative, take on this Rossini gem.

The action takes place in late 3rd century Palmyra, now part of Syria. In battle the Roman Emperor Aureliano defeats and captures the Persian Prince Arsace, commander of the Palmyrene Empire army. The Palmyrene Queen Zenobia is in love with Arsace and attempts to buy his freedom, but Aureliano will only free him if he can have Zenobia's love. She rejects his offer but eventually Aureliano, impressed by the devotion of the lovers, frees Arsace, and the opera ends happily.

Normally, in evaluating operatic performances I begin with the singers, but in this case I start with the conductor, Will Crutchfield, who clearly believes in this work and leads it with a real passion and commitment. He draws spirited and accurate playing from the orchestra, and fine singing from the chorus. True, I did get the feeling that some of the tempo selections are on the leisurely side, like the opera's closing number Copra un eterno oblio, but Crutchfield always seems to make his way with the score work. Of the cast members I was most impressed with the Zenobia of Jessica Pratt, a statuesque soprano whose First Act aria Non plangete was one of the high points of the performance. Indeed, her high notes and dramatic skills are stunning here and throughout. Equally convincing is the Aureliano of American tenor Michael Spyres. Excellent also is mezzo Lena Belkina in the trouser role of Arsace (actually the role was originally written for the famed castrato Giovanni Battista Velluti). The rest of the cast is quite fine too.

Because of the limited space in this theater, the orchestra pit is situated partly beneath the stage. The fortepianist, Lucy Tucker Yates, who provides continuo for recitatives, apparently could not be accommodated in the pit and so performs her role on stage, usually positioned to one side. She sometimes figures in the action in small ways, but limited lighting keeps her out of sight much of the time. There is also a cellist serving in the continuo role, David Etheve. Incidentally, it appears that Ms. Yates is quite versatile, being a soprano of considerable skill as well – she has sung Violetta in La Traviata in Milan and she sings in the bonus feature here.

Owing to the "completeness" and overall high quality of this recording, it is an easy recommendation, not only to Rossini mavens but to those with an interest in early 19th century Italian opera. The camera work, picture quality and sound reproduction are all first rate, making this a most desirable issue on technical grounds as well. In addition, there is the aforementioned bonus feature entitled Making of Aureliano in Palmira that features commentary by Crutchfield and others integral to the production.

Copyright © 2015, Robert Cummings