The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Poulenc Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

DVD Review

DVD Review

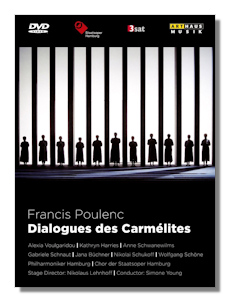

Francis Poulenc

Dialogues des Carmélites

- Alexia Voulgaridou - Blanche de la Force

- Wolfgang Schöne - Marquis de la Force

- Nikolai Schukoff - Le chevalier de la Force

- Kathryn Harries - Madame de Croissy

- Anne Schwanewilms - Madame Lidoine

- Gabriele Schnaut - Mère Marie de l'Incarnation

- Jana Büchner - Soeur Constance de Saint-Denis

Chor der Staatsoper Hamburg

Hamburg Philharmonic Orchestra/Simone Young

Nikolaus Lehnhoff - Stage Director

Arthaus Musik DVD 101493 Dolby Digital DTS LPCM Stereo Widescreen Anamorphic

Also available on Blu-ray Arthaus Musik 101494:

Amazon

- UK

- Germany

- Canada

- France

- Japan

- ArkivMusic

- CD Universe

- JPC

Dialogues of the Carmélites (1953-56) is without doubt Poulenc's magnum opus. There are few composers about whom you can say that a certain work stands apart from the others, representing their highest art. Perhaps Holst, with his mega-hit The Planets, is another case in point. Regarding Poulenc, it can further be observed that anyone familiar with his instrumental and other stage works but not with Dialogues of the Carmélites, will be astonished by the work's seriousness and expressive depth upon first encounter. It is, in a sense, Wagnerian, but not in sound or style-rather, in its meanings and subtleties. Its orchestration divulges healthy hints of Stravinsky and Puccini-an odd duo, I'll concede, but one that coalesces nicely. Yet, the music is pure Poulenc – Poulenc under the spell of deep religious conviction. The opera's story, taken from a screenplay by Georges Bernanos, based on the Gertrud von Le Fort novella, The Last on the Scaffold, which was in turn derived from actual events during and following the bloody French Revolution, would seem at odds with Poulenc's pre-1950s aesthetic sense.

Poulenc's music was generally bright or light or brilliant, or a combination of these characteristics. His two popular sacred works, Stabat Mater and Gloria, are certainly exceptions and suggest that when religion was the source of inspiration Poulenc became a different man. Dialogues of the Carmélites is often austere and sometimes quite profound, even in its more simple moments. The libretto, fashioned by the composer from the sources mentioned above, conveys a deeply-ingrained religious conviction and what most people today would regard as a fanatical altruistic sense. It also imparts a quite timely political message about government imposing its power-hungry will on the individual. Ah, and that's likely why this work remains so popular today.

The story centers on Blanche de la Force, who suffers from intense fear for her life as a consequence of premature birth. To seek peace Blanche joins the Carmelite convent, which eventually comes to be viewed with scorn and suspicion by the anti-religious, anti-clerical new Republic then comprising the French government. In the end, as the Carmelite nuns are facing the guillotine, Blanche, who had been on the lam, joins them fearlessly to face their awful fate.

Poulenc's music is often modest and understated, but always subtle and deftly scored. Sometimes it rises to the greatest heights of glory: the music from the last scene, when the nuns are executed (Salve Regina, mater misericordiae), is powerfully moving, full of intensity and religious devotion. But it must be said that the score throughout is consistently involving, with hardly a single misstep. The cast is strong here: Greek-born soprano Alexia Voulgaridou sings the role of Blanche with commitment and vocal beauty. Kathryn Harries is quite convincing as the prioress of the convent; her death scene (Act I, Scene IV) is utterly powerful in its emotional depth. Anne Schwanewilms as Madame Lidoine (who becomes prioress after the death of Madame de Croissy) and Jana Büchner as Sister Constance also turn in fine performances. Gabriele Schnaut is dramatically convincing and, to some, will sound fully appropriate with her matronly voice, but her vocal appeal is limited by a sometimes distracting wobble.

Australian conductor Simone Young draws excellent performances from the Hamburg Philharmonic and from the Chorus of the Hamburg State Opera. The camera work is quite fine and Raimund Bauer's sparing sets (a chair here, a bed there), convey a timeless sense in their barren look. The lighting, by Olaf Freese, is more provocative in its blue and white and misty qualities. Andrea Schmidt-Futterer's costumes are generally appropriate, though the outfits worn by Blanche's father, the Marquis, and her brother, Le chevalier de la Force, look more like turn-of-the-20th-century styles. Nikolaus Lehnhoff's stage direction is effective as usual and virtually every aspect of the production here, including the sonics, is excellent. Highly recommended.

Copyright © 2010, Robert Cummings.