The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Lully Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

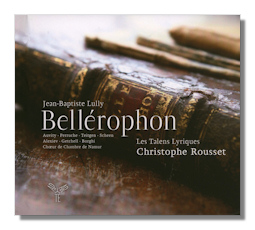

Jean-Baptiste Lully

Bellérophon

- Ingrid Perruche, soprano (Sténobeé)

- Céline Scheen, soprano (Philonoé)

- Jennifer Borghi, mezzo-soprano (Argie/Pallas)

- Cyril Auvity, tenor (Bellérophon)

- Robert Getchell, tenor (Bacchis/La Pythie)

- Evgeniy Alexiev, baritone (Pan/Jobate-Le Roy)

- Jean Teitgen, bass (Apollon/Amisodar)

Chamber Choir of Namur

Les Talens Lyriques/Christophe Rousset

Aparté AP015 2CDs + Book

Hats off to Rousset, his musicians, and Aparté for this wonderful two-CD release (the only one in the current catalog) of Lully's Bellérophon. It's a lively, substantial, spectacular and approachable five-act classical allegory with a libretto by Thomas Corneille (1625-1709), younger brother of the more celebrated Pierre, who had, eventually, to call on the help of Fontelle (1657-1757) and Boileau (1636-1711) so demanding was Lully. His previous librettist, Quinault, had been "expelled" from the French court for an apparent slight to one of Louis XIV's favorites, Madame de Montespan, in his (and Lully's) opera Isis, first performed in 1677. Bellérophon itself was performed for the first time at the Palais Royale in Paris on January 31, 1679. After a successful run lasting nine months, it eventually fell into obscurity (though not before revivals in the 1680s, 1700, 1718, 1728, 1745 and even in 1773) and was not performed again until last year (2010) after Christophe Rousset had found an old edition neglected, it seems, because shunned by at least one earlier musicologist, who should have known better. Making his own version, Rousset and Les Talens Lyriques mounted a production in Versailles. At one or more of these performances the present recording was made.

Although not one of Lully's first tragédies lyriques, Bellérophon was one of his first to appear in print. So this release has musicological as well as musical significance. The myth of Bellérophon was a simple one: he rode Pegasus to defeat the Chimera. This was a clear metaphor for Louis XIV's military victories in the Netherlands over the Dutch, the Spanish, and the Holy Roman Emperor. Slightly less expected, perhaps, was the implicit plea for restraint, mercy, clemency on the king's part – Bellérophon showed restraint and moderation when dealing with those he defeated.

Indeed, restraint is characteristic both of the opera as conceived, and of Rousset's realization of it. Certainly it begins with the usual dotted rhythms, which quickly double in speed; there are the usual end of act flourishes with unpitched percussion; there is an expected alternation of aria, recitative, chorus and short instrumental parts. But, a touch of breathiness of one or two of the sopranos aside, the nasal earnestness of some performances is totally absent. There is a sweetness and gentility that characterize this performance, and lead us into some very pleasant territory indeed… listen to love duet between Bellérophon (the excellent tenor, Cyril Auvity) and the equally compelling Céline Scheen (soprano) as Philonoé [CD.1 tr 22]. They have sweetness in abundance; yet it's tempered by reserve and enhanced by the very exactness and penetrating clarity of articulation and enunciation that in fact characterize the whole production.

It's possible that Lully's melodies and textures are more than a mere or incidental glance towards Louis XIV's military exploits. The tempered style of the soloists, here, in particular can be interpreted as a recognition that a peaceful and successful king (in the context of seventeenth century European absolute monarchs!) was likely to sponsor greater and greater artistic endeavor. So the stately pace of the music – and its performance here – communicate a dignified sense of responsibility beyond the immediate concerns of war.

Rousset has infused this account with an almost perfect blend of excitement, vigor, sinew with gravitas, detachment, loftiness. This is in no small part due to the excellence of his soloists with Ingrid Perruche (Stenobée) and Jean Teitgen (Amisodar) also offering memorable performances. For all the events' predictability (especially to contemporary audiences, who would have known the myth), these forces have a dramatic spontaneity and wit which are coupled only with their technical brilliance and sense of presence. Splendid.

Just as felicitous is the balance (and surely we have Corneille to thank for this) between spoken text, action, dance, "pure" music and so on. There's not a moment (of this performance) where our attention wanders, or where we're tempted to speculate on how something might have been achieved differently. There's a transparency to Lully's writing which resounds very successfully in Rousset's conception of Bellérophon. It might even not be suggesting too much to liken the opera to more durchkomponiert works of several decades later – in ways in which Weber's operas take off from where Mozart's left off, for instance. It might also not be too fanciful to remember that for all the sycophancy in which Lully engaged (or felt forced to engage), this opera leaves enough of a gap between his forehead and the floor for his wider sense of responsibility to music and his Italian origins to be clearly visible. That Rousset's conception is aware of this, though it barely tries to accentuate it, is to everyone's credit.

The two CDs come in a lavish hardback book with synopsis, nicely-printed libretto in French, English and German, essays on the opera's background, the performers. The acoustic is as clean, if somewhat close, giving away little of its live source. This is a CD which lovers of Lully cannot afford to ignore; indeed, nor can anyone interested in Baroque opera in general. Even were it not for the musicological interest in a world première recreation of such an important work, the musical suaveness, eloquence and delicacy of Bellérophon – especially in the hands of such eminences as these soloists, Les Talens Lyriques and the Chamber Choir of Namur with Christophe Rousset – make it a release that recommends itself.

Copyright © 2011, Mark Sealey.