The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Machaut Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

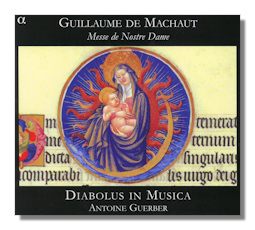

Guillaume de Machaut

Messe de Nostre Dame

Diabolus in Musica/Antoine Guerber

Alpha Productions ALPHA132

Machaut's elegant and glorious Notre (or, more properly, Nostre) Dame Mass is still emblematic of events 40 years ago in the 'early' music field. It was one of the first works to which attention turned during the great resurgence of interest and explosion of expertise in performing medieval music in the 1960s. Perhaps because this is the first complete polyphonic mass known to have been the work of one composer and preserved in its entirety. Perhaps because two or three generations ago it sounded so splendid, new – exotic, almost. Certainly striking. There are currently fewer than a dozen recordings in the catalog; these do not include the one by Noah Greenberg and the New York Pro Musica, an iconic recording central to the early music revival. Like any modern symphony or chamber work, Machaut's hour-long work admits of almost as many interpretations as there are interpreters.

On this CD we get a robust and highly convincing interpretation from the ever enterprising eight-person (all male) French group, Diabolus in Musica, under their director Antoine Guerber. 'Diabolus in Musica', by the way, implies the E-B (or the modern F-B) tritone, or augmented fourth, used throughout Western music to establish dissonance – the devil, to be kept out of music at all costs. The group's is a direct, intimate and penetrating approach. Although the textures which the ensemble consistently achieves are sonorous, they are neither fanciful, nor over-rich. The tempi are refreshingly slow, unhurried and allow exposition of the importance, weight and impact of every syllable; for the words are of the utmost importance.

Machaut (c.1300-1377) was a contemporary of Chaucer. It's tempting to see parallels between Chaucer's wry adaptability to the succession of disasters of the century (plague, famine, war, social instability) and the almost sanguine response to such suffering of Machaut, who was canon at Reims cathedral from 1337 until his death 40 years later. It's to what was surely Machaut's inner strength, his faith, certainty of the rightness of a devoted life and later salvation, that Guerber and Diabolus in Musica respond in this excellent performance.

It's just as important to bear in mind how much of a change in liturgical life this mass represents. This may be surprising: Machaut was following on the tradition established during the composer's first years in his post at Reims of singing a plainchant votive Marian mass; yet polyphony was discouraged. In 1352 Pope Clement VI funded the Chapter at Reims with twelve cantors of sufficient skill and experience to provide Machaut with executors of his more ambitious and resplendent music. It did, though, take him another dozen years or so before the Messe de Nostre Dame was written. But can there be no connection?

By refusing to overplay their hands, by judicious restraint, and by meticulous articulation of every note in undemonstrative yet highly expressive phrasing Diabolus in Musica seems to have captured not only the rigor and joy which Machaut employed in this task. But these wise musicians are also at one with the novelty and innovative impact which the mass must have made when first sung. The recording – which is crisp and atmospheric – was made in a low-ceilinged location at the Abbey of Fontevraud. This acoustic enhances the music-making. Ultimately, it's the perspicacity and skill of Guerber and his singers that makes this recording so successful and satisfying. Listen to the lines and varying intensities of the Gloria [tr.3], for example. As much gentle and yet lavish breath as unselfconscious poise. Yet without drawing any teeth: the singers in Diabolus in Musica are real individuals performing as such. No attempt to submerge or efface their vocal personalities. Nor yet to impose wayward, unnecessary color. The music comes first and last – and is somehow interpreted for what it is: a liturgy in which to be involved. Yet as much as an object of beauty and wonder as a rather austere – No, restrained – service.

Plainchant is interspersed with polyphony. The flow is never interrupted and onto the whole work is conferred a unity under the direction of Guerber that makes attentive listening particularly rewarding. Perhaps this is due in part to the pronunciation adopted… the Latin pronounced as was the 'Middle French' – for it is now thought that clerics in a setting like Machaut's at Reims used the vernacular. Note, too, that there are two motets: Rex Karole by the contemporary Philippe Royllart [tr.8], and the anonymous Zolomina/Nazarea/Ave Maria [tr.15] interspersed with the mass.

The booklet that comes with this CD is up to the usual standards with introductory essays in French and English; the text of the mass is in Latin, modern French and English. So here's a recording that can be unequivocally recommended both for anyone who has yet to discover the glorious intensity and transparent beauty of this music; and who may have one or more other recordings in their collection (that by Oxford Camerata under Jeremy Summerly on Naxos 8.553833 is otherwise a good first stop) but wants to get to know multiple perspectives. Don't wait!

Copyright © 2008, Mark Sealey