The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

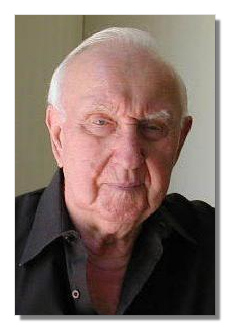

Benjamin Lees

(1924 - 2010)

Benjamin Lees' (January 8, 1924 - May 31, 2010) musical output followed a consistent path over four decades, since his earliest orchestra scores of the 1950s. Classical musical structures form the basis of his works, expertly crafted and honed into his own language, always tonal, but exploring the full range of tonality through development of subject matter. Inversions, stretti, canons, fugues, melodic and harmonic exploitation of intervals; all of these were ordnance in the Lees armory but Lees the technician was always the master, not the servant of his art. And it is as his art has grew that he, as it were, "slipped the surly bonds of earth;" each new work representing a graceful display of compositional flight in all its aspects.

Lees' chosen instrument was the orchestra, with five symphonies and numerous concertante works making up the core of his output. The Fourth Symphony, "Memorial Candles" (1985), in homage to the victims of the Holocaust, with a soprano setting of poems by one of the survivors, is a "cri du coeur" of visceral and dramatic intensity. The stark realism of these poems is graphically illustrated by the orchestra which captures terror in all its aspects; fear, revulsion, anger, and finally sad resignation find voice through such devices as fluttered brass fanfares, shrieking strings, chiming celestas, and a solo violin, representing the beleaguered soul. This fifty-minute work opened up new frontiers for Lees, as did Portrait of Rodin (1984), a suite of tonal impressions of coloristic sonority. And Lees the miniaturist is found in Mobiles (1989), a series of linked musical thumbprints based on moving abstract sculptural designs.

The Fifth Symphony "Kalmar Nyckel" (1988) follows a more traditional structure, commemorating the arrival of Swedish immigrants to Delaware in the 1600s. Its hallmarks are rhythmic tension, intervallic interrelationships (especially octaves and fifths) and compactness of design. The initial mood of apprehension gradually yields to growing and expectation, culminating in a gloriously upbeat finale.

Amongst the finest of Lees' mature works is the Concerto for Brass Choir and Orchestra (1983), his third essay in a series of pieces for groups of concertante instruments with orchestra. Lees' skill in exploring instrumental contrasts, harmonic intervals (again fifths and octaves) while developing his materials is strongly evident here.

The Louisville Orchestra gave early support to the composer's career by recording his Second and Third Symphonies, and the Concerto for Orchestra (1959). The frequency with which his music is performed is testimony to its continuing popularity, with well-known conductors of major and regional orchestras mounting performances, not only of new commissions but also of earlier works.

Of his String Quartets, the Fourth (1989) demonstrates a favorite Lees device: continual evolution. Classical in structure, described by the composer as "a landscape of shifting meters and turbulence," it is a masterful exposition of virtuosity, elegance and poise. The second fast movement is played pizzicato throughout and the final movement with its "hurly burly" of ideas and dissonant harmonies is a model of abstract form within tonal limits.

Always a disciplined artist, Lees kept faith with his values and beliefs. For him, music should be approached and appreciated on its own terms. Programmatic backgrounds, ethnic considerations and "Americana" were not germane to his musical credo. His lifetime of exploration was dedicated to the search for his own ideal of artistic truth. The "Lees style" is instantly recognizable and every work is possessed of lofty grandeur. ~Courtesy of Benjamin Lees