The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

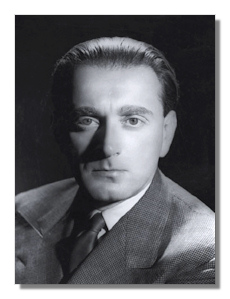

Miklós Rózsa

(1907 - 1995)

Although long resident in the United States, Miklós Rózsa (April 18, 1907 - July 27, 1995) belongs among the great 20th-century Hungarian composers: Bela Bartók, Zoltán Kodály, László Lajtha, Ernő Dohnányi, György Ligeti, and György Kurtág.

Born in Budapest to a wealthy industrialist, Rózsa spent much of his childhood on his family's country estate and grew up around Hungarian peasant music. Unlike Bartók and Kodály, Rózsa did not have to painstakingly retrieve and recover Hungarian folk music so that he could turn it to his own ends. It belonged to his natural musical bent and environment. After private instruction in piano, violin, and viola, in 1926 Rózsa began studying at the Leipzig Conservatory both composition and musicology, the latter a discipline that would serve him well during his career as a film composer.

Within three years, Breitkopf & Härtel published his first compositions, and in 1931, he moved to Paris, where despite successes in the concert hall, he found it difficult to make ends meet. His friend, the Franco-Swiss composer Arthur Honegger, found him work in films, and Rózsa hooked up with Alexander Korda and shuttled between Paris and London. At the outbreak of the war in Europe, Rózsa went with Korda to Hollywood to score the classic film Thief of Baghdad (1940). He went on to write music for several more classics including The Jungle Book (1942), Five Graves to Cairo (1943), Double Indemnity (1944), The Lost Weekend (1945), Spellbound (1945), The Naked City (1948), Adam's Rib (1949), The Asphalt Jungle (1950), Quo Vadis (1951), Ivanhoe (1951), Julius Caesar (1953), Lust for Life (1956), Ben-Hur (1959), El Cid (1961), and Providence (1977), making his final bow in Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid (1981). He had two "hits," the so-called Spellbound Concerto and the theme to the American television series Dragnet (based on the title cue to Rózsa's Brute Force).

As a film composer, Rózsa – along with Franz Waxman, Bernard Herrmann, and Elmer Bernstein – helped turn Hollywood movie music from neo-Strauss and neo-Tchaikovsky to more modern idioms. He excelled in several genres: fantasy, film noir, historical dramas, Biblical epics, and his lone New Wave masterpiece, Providence. He was nominated for an Oscar 16 times and won 3.

However, his concert output also reaches very high quality. He didn't write much. To some extent, his movie work got in the way, but I always sensed that he characteristically took a lot of time waiting for inspiration and polishing and revising like a demon. He probably would have had a relatively small output in any case. Like Vaughan Williams, he usually writes music based on folk song without quoting actual folk tunes. He produced one repertory staple, a violin concerto for Heifetz (1953), but almost all his concert work deserves a wider hearing. These include a symphony (1930, rev. 1993), concerti for piano (1966), cello (1968), viola (1979), and for violin and cello (1966), the Concerto for Strings (1943, rev. 1957), Tripartita (1972), and several smaller-scaled orchestral works. He also excelled in chamber music, producing a string trio (1927, rev. 1974), Duo for violin and piano (1931), a sonata for 2 violins (1933, rev. 1973), a piano sonata (1948), and two string quartets (1950, 1981). Toward the end of his life, Rózsa suffered a stroke which made composing large works too taxing. However, he continued to compose, turning out a beautiful series of solo sonatas for flute (1983), violin (1985), clarinet (1986), guitar (1986), ondes martinot (1987), oboe (1987), and an Introduction and Allegro for solo viola (1988).

His music – highly lyrical and dramatic – usually alternates between melancholy brooding and explosive dance. When given a chance, it has proven that it can connect with an audience, and yet hardly anybody programs it. Fortunately, you can now find most of his major work on CD. ~ Steve Schwartz

Recommended Recordings

rep

rep

- Recommendation to come…