The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Find CDs & Downloads

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic - CD Universe

Find DVDs & Blu-ray

Amazon - UK - Germany - Canada - France - Japan

ArkivMusic-Video Universe

Find Scores & Sheet Music

Sheet Music Plus -

Recommended Links

Site News

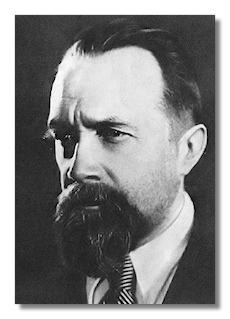

Nicolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky

(1881 - 1950)

Alive during an era of such world-renowned Russian names as Dmitri Shostakovich, Serge Prokofieff, and Aram Khachaturian, it is inevitable that Nicolai Myaskovsky (April 20, 1881 - August 8, 1950) has become lost in the shuffle. Myaskovsky sits nowadays in obscurity while the Soviet Union's "holy trinity" of composers generates euphoria amongst performers, musicologists, and the listening public. But room can no doubt be made in the concert hall for others who were respected in their time, respect that Myaskovsky rightfully earned.

Nicolai Yakovlevich Myaskovsky was born in Novogeorgievsk, a Russian army fortress situated near Warsaw, Poland. Myaskovsky's father Yakov was a military engineer, which led his family to change residence several times during Nicolai's childhood. The Myaskovskys lived at Novogeorgievsk until 1888, Orenburg near Kazakhstan from 1888-9, and Kazan in central European Russia from 1889-93. Nicolai, as was expected, received his preliminary and secondary education in military schools, including at Nizhni Novgorod and St. Petersburg. Most significantly, he received piano instruction from his aunt Yelikonida, who sang at the St. Petersburg Opera and took on the role of female guardian after his mother's death.

Myaskovsky entered a military engineering institute in 1899, but music was obviously his calling. Through recommendation by Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakoff and Sergei Taneyev, Myaskovsky began harmony lessons with Reinhold Glière while his battalion was training in Moscow. The battalion relocated to St. Petersburg, where he studied counterpoint, fugue, and orchestration with Glière's friend, avant-gardist Ivan Kryzhanovsky, who co-founded the influential "Evenings of Contemporary Music." While in St. Petersburg, Myaskovsky had first-hand experience with the newest European musical trends. As he later wrote, "the atmosphere, extraordinarily tense with musical searching, and the supercritical evaluation of results could not but infect me."

In 1906, Myaskovsky neared the end of his mandatory army service and was accepted to the St. Petersburg Conservatory at a rather late age of 25. He was transferred to the army reserves in 1907 and continued his studies despite a rule that barred military personnel from civilian academic programs (simply no one noticed). Myaskovsky had composed in spurts before his Conservatory tenure, writing piano pieces and songs for piano and voice. Little of this work was performed or published. The seeds for a compositional future were sown, however, in 1908 when Myaskovsky wrote his First Symphony (in C minor, Op. 3), not coincidentally his first complete work for orchestra. Gaining direction from such men as Rimsky-Korsakoff and Anatoly Lyadov (whom he greatly disliked), Myaskovsky settled into the form that he would make central throughout his life.

In 1911, Myaskovsky graduated and began work as the St. Petersburg correspondent for Muzhyka, a progressive musical journal. The work further exposed him to western composers and influenced his own style, although the political climate would eventually limit his creativity. Myaskovsky had written a Second Symphony (in C-sharp minor, Op. 11) and Third Symphony (in A minor, Op. 15) by 1914, the year he was mobilized as an army officer during the First World War. He spent time at the Austrian front, where he was wounded and experienced shell shock, before reassignment to Moscow until 1921.

If his Soviet autobiographical writings are indeed accurate, Myaskovsky was politically a liberal and supported the October Revolution. But in a twist of irony, most of the "old guard" had relocated to other countries, including Stravinsky, Rachmaninoff, Scriabin, and Myaskovsky's classmate, Serge Prokofieff, with whom he maintained contact. By remaining in the Soviet Union, Myaskovsky became a symbolic bridge connecting the old Russian artistic world to the new post-revolutionary version. In 1921, he became a professor of composition at the Moscow Conservatory, where he was highly regarded until his death, and his symphonies were an ongoing staple of the concert repertoire.

Myaskovsky wrote 27 symphonies, often composed at a blistering pace (he was known to work on two or three symphonies at once). The symphonies were heard regularly in the Soviet Union and frequently performed abroad. Symphony No. 5 (in D major, Op. 18, 1918) was in fact called the "first Soviet symphony" by Russian critics, although Myaskovsky was not a clear-cut product of the October Revolution like Shostakovich. His symphonies were indeed highly modern works that rivaled western and Soviet colleagues in popularity. In 1935, the Columbia Broadcasting System conducted a survey of its radio listeners, asking which modern-day composers would retain their fame into the next century; Myaskovsky was one of the top ten selections, amongst de Falla, Kreisler, Prokofieff, Rachmaninoff, Ravel, Shostakovich, Sibelius, Richard Strauss, and Stravinsky.

Although highly respected by the Soviet musical community, Myaskovsky was named in the infamous 1948 attacks on "formalism" and "bourgeois decadence" by the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party. Myaskovsky had been largely "conformist" in writing music that satisfied government policy while eschewing propaganda and keeping his unique voice; but no prolific composer was spared from the denunciations and Myaskovsky joined Shostakovich, Prokofieff (who had returned to the U.S.S.R.), and Aram Khachaturian (his former student) as cultural advisor Andrei Zhdanov's main targets. The dignified Myaskovsky refused to take part in hearings or "repent" his sins, imposing a death sentence on his compositional career. His health was already failing by this time and he died of cancer in Moscow on August 8th, 1950, having written a large body of work and taught an entire generation of Soviet musicians. Myaskovsky was "rehabilitated" by the Soviet authorities after his death and won a posthumous Stalin Prize for his Cello Sonata No. 2 (in A minor, Op. 81, 1948). He won the Stalin Prize six times, unmatched by any other composer.

While a familiar name to musicologists, Myaskovsky's reputation has waned considerably since his death. His music is seldom performed in concert, scores are rarely found in libraries, and recordings are incredibly scarce. Myaskovsky's canon admittedly fluctuates in quality; this is unavoidable for a man who wrote symphonies, concerti, string quartets, solo piano music, works for chorus, and other arrangements by the truck load. Soviet musicologist Boris Asafiev was correct in speaking of the "prism" through which Myaskovsky worked; he was a highly knowledgeable musician who identified the merits of other composers (as wide as Shostakovich, Grieg, and Wagner) and synthesized these merits into his own language While his experiments did not always succeed, Myaskovsky proved an open-minded intellectual whose scores often became a laboratory for the various directions that music could take.

So why, exactly, has Myaskovsky become the only name to plummet from that list of ten composers in the CBS radio survey? One reason, perhaps, is that Myaskovsky died just two years after the 1948 Zhdanov Decree; his music was knocked out of the repertoire almost simultaneously with his passing. Although efforts were made to rehabilitate his music in the Soviet Union, Myaskovsky was no longer around and he did not have an estate (he never married or had children) to promote his work Another dilemma is the vastness of Myaskovsky's canon; since Myaskovsky has fallen out of the repertoire, few music directors or recording specialists are willing to dig through his 87 opus numbers (including 27 symphonies) and separate "good" works from "not-so-good" works. With only fifteen symphonies by Shostakovich, seven by Prokofieff, and three by Khachaturian to choose from, orchestras and recording labels have a built-in excuse not to get their hands dirty.

In recent years, Myaskovsky has won support from conductors like Yevgeny Svetlanov, who recorded his entire cycle of symphonies, and Neeme Järvi. Myaskovsky, however, remains largely ignored as a composer and best remembered as a teacher who influenced such men as Aram Khachaturian, Dmitri Kabalevsky, Vissarion Shebalin, and Boris Tchaikovsky. Playing such a key role in the education of composers is no disgrace, but his extensive body of work seems to be crying for rediscovery. Only time will tell if his music is rescued from the archives increasingly caked over with dust. ~Paul-John Ramos

Recommended Recordings

Symphonies

Symphonies

- Symphonies #15 & 27/Musical Concepts 1021 (Olympia OCD741)

-

Evgeni Svetlanov/Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #16 & 19/Musical Concepts 1022 (Olympia OCD742)

-

Evgeni Svetlanov/Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #17 & 21/Musical Concepts 1023 (Olympia OCD743)

-

Evgeni Svetlanov/Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra

- Symphonies #24 & 25/Naxos 8.555376

-

Dmitry Yablonsky/Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra

- 27 Symphonies; Overtures, Suite, Lyric Concertino, Symphonic Poems, Sinfoniettas, Divertimento, Serenade, etc./Warner (Melodiya) 2564-69689-8

-

Evgeni Svetlanov/Russian Federation Academic Symphony Orchestra, USSR State Academy Orchestra

Concertos

- Concerto for Cello w/ Prokofieff & Rachmaninoff/EMI Great Recordings of the Century 380012-2

-

Mstislav Rostropovich (cello), Malcolm Sargent/Philharmonia Orchestra

- Concerto for Violin w/ Weinberg Violin Concerto/Naxos 8.557194

-

Ilya Grubert (violin), Dmitry Yablonsky/Russian Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra

- Concerto for Violin w/ Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto/Philips 473343-2

-

Vadim Repin (violin), Valery Gergiev/Kirov Theater Orchestra