The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

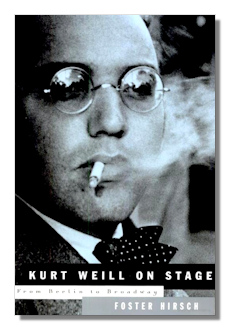

Kurt Weill on Stage

From Berlin to Broadway

Foster Hirsch

New York: Alfred A. Knopf. 2002

Paperback. 406 pages.

ISBN-10: 0879109904

ISBN-13: 978-0879109905

Summary for the Busy Executive: A corrective view of Weill, a long time coming.

Despite what anybody thinks of his music, Kurt Weill has to be reckoned as one of the most protean dramatic composers of the century. From a family that had lived in Germany for at least seven hundred years and a cantor's son, Weill began as an avant-gardiste Busoni pupil (he would have studied with Schoenberg, had the money been available), caught up in Expressionism and at the fringes of atonality. A political liberal, however, he became dissatisfied with the ethical implications of writing music only for connoisseurs and sought to broaden his appeal by combining elements of popular song with his "priestly" training. He sought out like-minded spirits as collaborators. He most famously (and most fractiously) partnered with the poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht to produce such classics as Berliner Requiem, Mahagonny-Songspiel, Dreigroschenoper, Happy End, Der Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, Die sieben Todsünden, and the "teaching pieces" Der Lindberghflug and Der Jasager. Most critics consider them landmarks of the Modern stage and icons of the German Twenties.

When the Nazis came to power, Weill wisely fled, first to France and England, finally arriving in the United States. Looking for opportunities, he settled into a career on Broadway and here, after a somewhat shaky start, came up with Knickerbocker Holiday, Lady in the Dark, One Touch of Venus, Love Life, Street Scene, Down in the Valley, and Lost in the Stars. He died at the relatively young age of fifty. At least three of his American songs, "September Song," "Speak Low," and "My Ship" have become pop standards.

Because of Weill's forced emigration, scholars have tended to separate his career into two halves: Europe and America. They usually show a preference for one period or the other: the classical critics going for the European and the musical critics and historians preferring the American. However, Weill has also been fortunate in having at least two strong champions: David Drew and Kim Kowalke, who although they made their reputations in the European works, don't slight the American ones. To me, Weill's greatest, most thoroughly-realized pieces are his Brecht collaborations, but that doesn't mean that his other scores turn to chopped liver. Foster Hirsch, a film and theater scholar, takes a balanced view, and in fact argues for Weill's career as a seamless whole. He sees Weill, above all, as a creator who changed the relation between music and drama or the dramatic function of music just about every time he came to bat. From the Expressionist Der Protagonist and Der Zar lässt sich photographiert to the Singspiels Dreigroschenoper and Happy End, to the "epic opera" of Der Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny, to the "sung ballet" Die sieben Todsünden, the play with music Die Silbersee, Weill continually innovated.

When he got to the United States, he studied the American musical stage. He concluded that the Met and the standard opera circuit would be hostile to his kind of experimentation but sensed that the Broadway theater might be open to his kind of innovation, particularly when he saw Porgy and Bess during its initial run. It wasn't, as Weill's detractors have so often advanced, a matter of only making money. One also must remember Weill's tremendous admiration for Offenbach. Weill's shows, with the exception of Lady in the Dark, never managed better than a respectable run. However, their influence on other composers of musicals was enormous. Johnny Johnson, Weill's first American show, despite its madcap catalogue of parlor waltzes, cowboy songs, sentimental ballads, tangos, foxtrots, and so on, still has the whiff of Europe about it – a satirical Kabarett. It feels as if Weill is learning the basics of his new musical territory. Knickerbocker Holiday is a "book" musical with emphasis on a well-made book, something that influenced Richard Rodgers in particular (Weill was often jealous of Rodgers's success, which he felt came at the expense of his own). Lady in the Dark was Weill's big American smash and the piece that established him on Broadway and enabled him to take the risks that were his reason for writing. Of course, Lady in the Dark itself was hardly a safe bet. Not only was it "about" psychiatry (daringly new for the time) it was also constructed as three mini-operas ("dream sequences"). One of the big hits of the show, "My Ship," also provides the dramatic key. It's heard in bits and snatches throughout and only in full at the end. Love Life about the ups and downs of a marriage is, along with Rodgers and Hammerstein's Allegro, is one of the early "concept" musicals, siring such descendents as Sondheim's Assassins and Pacific Overtures. Street Scene takes a deadly serious play by Elmer Rice and turns it into something very close to opera. Lost in the Stars, like Carousel, hovers in a fluid space between musical and opera, although Weill comes closer to opera than Rodgers does, with a magnificent use of chorus. This hardly seems the work of a guy out for a buck. There are easier ways to make a dollar. Furthermore, Weill continues pushing and discovering new ways to make music drama. He's even more innovative in that way than in his German period.

Hirsch makes all this clear. Even though he flirts with one of my pet peeves – reciting plot – he at least uses it to support his argument. Hirsch isn't, however, a musician and makes no claim to be. He does, however, have an appreciative, analytical ear, especially for what makes a play work. I don't at all agree with his assessment of Lost in the Stars as often "routine," but he does sense the weakness of Maxwell Anderson's play. The music, to which Hirsch is also lukewarm, I think among the best of Weill. But that's a matter of taste. If you want musical analyses, go to Drew or Kowalke. Hirsch has, however, staked out valuable territory of his own.

Copyright © 2010 by Steve Schwartz.