The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

-

Introduction

Acoustics

Ballet

Biographies

Chamber Music

Composers & Composition

Conducting

Criticism & Commentary

Discographies & CD Guides

Fiction

History

Humor

Illustrations & Photos

Instrumental

Lieder

Music Appreciation

Music Education

Music Industry

Music and the Mind

Opera

Orchestration

Reference Works

Scores

Thematic Indices

Theory & Analysis

Vocal Technique

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

Book Review

Book Review

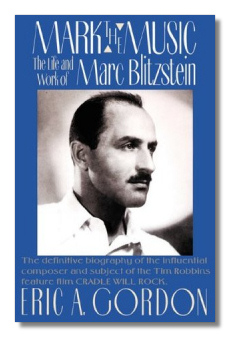

Mark the Music

The Life and Work of Marc Blitzstein

Eric A. Gordon

New York: iUniverse. 2000. 644 pp

ISBN 0595092489

Summary for the Busy Executive: Marking history, rather than music.

As far as I know, Gordon has produced the first book-length study of American composer Marc Blitzstein. An historian by training, Gordon has done his work at the eleventh hour. Most of Blitzstein's contemporaries are dead or soon will be. Gordon has assiduously sought the survivors out, and the book benefits from the wealth of first-hand information.

The public has largely forgotten Blitzstein's music – a shame, really. Blitzstein began as a hard-core Modernist, became a pupil of Schoenberg, and produced several avant-garde pieces in the Twenties and early Thirties, notably a wonderful piano concerto. However, like many artists during the Depression, he fell in with the American Communist Party. Blitzstein, however, was no political theorist. Although his ardor for Communism at this time was sincere, it was mostly heart and little head. I don't believe he read much Marx, for example. Instead, an almost Biblical rage against the failures of capitalism and American social injustice fueled him. After all, at the time no major political party other than the Communist concerned itself with things like exploitation of migrant workers or civil rights for blacks. Republican leaders had sold out in the Nineteenth Century with the election of Hayes, which put the kibosh on Reconstruction. In Roosevelt's New Dea l, Democrat leaders kept power by holding onto both a Southern base and Northeast and Midwest industrial labor. The Progressive movement had largely ignored blacks and unskilled labor and thus left the Communists the only game in town.

At any rate, the Party strictures on art at the time happened to coincide with Blitzstein's own artistic concerns. He wanted his music to reach a large number of people so that he could help change society. He realized early that the "hard" modern music he had written up to that point turned off the audience he wanted to reach. On the other hand, he didn't want to write treacle or what he despised as corrupt "moon-June" pop. The "worker songs" by German composer and leftist Hanns Eisler gave him some direction. He then wrote his first success – at the time, a succès de scandale – the "union opera," The Cradle Will Rock, to his own libretto. The play is a Brechtian vaudeville of connecting skits on the theme of "prostitution" (of church, academia, medicine, and so on), set in an idiom that plays brilliantly off popular forms like ragtime, "Hawaiian" serenades, "jazz" croons, parlor waltzes, and blues and yet retains a Modern edge. In the late Forties, he broke with the CP over what he regarded as artistic interference but kept his populist orientation, proving, I believe, that art and independence of conscience meant more to him than the momentary political shift. Blitzstein in many ways cleared the path for Leonard Bernstein, although his music is much too good to be a mere adjunct. It's so good, in fact, that Bernstein stole from Blitzstein (Bernstein stole from a lot of good people – Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky, Hindemith, Copland – but through some alchemy made the steals his own). Blitzstein, recognized as one of the stars of the younger generation and working mainly in something close to popular theater, should have had it made. In fact, he struggled financially almost all his life, despite his artistic accomplishments.

Part of this was due to the fact that he felt compelled to write his own libretti. In contrast to his considerable musical facility, he was no playwright, and he knew it. On the other hand, he had the acumen to recognize when something "worked" theatrically. He just had to get there. As a result, he delayed works for years simply because he couldn't get a story or a character that worked right. Why he didn't collaborate, especially when he himself thought it a good idea, remains mysterious. Ironically, his greatest popular success, his unsurpassed translation of the Brecht-Weill Threepenny Opera (even the English title is Blitzstein's), is a collaboration of sorts. Doubly ironic is the fact that following Schoenberg and his disciples, he started out dismissing Weill's music as cheap and tawdry. By the Forties, however, he had come around, at least to Weill's European work. Brecht purists may sniff at Blitzstein's work, but for me it is the only Dreigr oschenoper translation that doesn't sound like one (about the recent Broadway production with Alan Cummings and Cyndi Lauper, don't ask). It is beautifully idiomatic and fiercely clever English lyric, worthy of Ira Gershwin, Lorenz Hart, and Johnny Mercer. It also possesses a raffishness thoroughly consistent with Brecht's whores and highwaymen.

Still, Blitzstein's main achievement remains his original work, too little known: The Cradle Will Rock, No for an Answer, Regina, the Airborne Symphony, Juno, This is the Garden, Native Land, Reuben Reuben, Freedom Morning, and especially his opera on Sacco and Vanzetti. At present, recordings are pitifully few, although his achingly lovely "I Wish It So" from Juno enjoys recordings from a few enterprising singers.

I doubt, however, this book will rekindle interest. Gordon, an historian rather than a musician, other than noting composition history, performances, and critical and public reception, leaves the music alone. Instead, he concentrates on the milieu of left-wing musical circles in New York, in which Blitzstein played a leading role. He confines his discussion of Blitzstein the creator to noting where and when and discussing the political implications of Blitzstein's libretti. In short, he fails to give us the main reason for caring about Blitzstein in the first place. After all, Earl "Ballad for Americans" Robinson in many ways would illustrate the same history (Gordon has indeed written a book on him), but his music has dated horribly. Blitzstein's music still lays artistic claim on us. Nevertheless, if you want to know something about art from the Thirties left, Gordon can tell you many interesting things and in detail. The research runs deep and wide, and Gordon m anages to keep his story clear and compelling. A solid piece of history.

Copyright © 2006, Steve Schwartz.